Nicole Asbury Washington Post Feb 2nd 2024

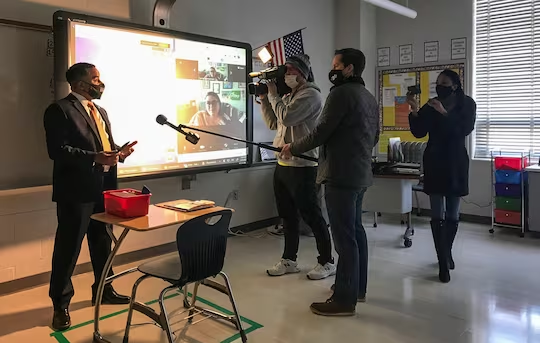

Montgomery County Schools Superintendent Monifa B. McKnight stepped down Friday amid questions about how the district handled sexual harassment, bullying and other allegations involving a former principal.

McKnight — the first woman to serve as the head of Maryland’s largest school system — said that she reached “a mutually agreed separation” with the county school board, effective Friday. She is departing about two years into a four-year contract with the district that was set to end in 2026.

“I have felt over the past few months, there has been a distraction,” McKnight said. “When the focus is no longer on whom I have agreed to serve, I must control my fate.”

The Montgomery school board met in closed session Friday afternoon to receive legal advice and get information on the status of an unnamed employee. Later, the board said it wished McKnight well in the next chapter and it would “work together with staff to ensure a smooth transition.”

Brian Hull, the district’s chief operating officer, will serve as acting superintendent. The school board plans to name an interim superintendent on Tuesdayand launch a national search for a new leader“in the coming days.”

“We must rebuild trust, begin to heal, and ensure that our school system is equipped to serve the students, staff and families who make up our great school community,” theschool board said in a statement.

McKnight’sdeparture comes weeks after shesaid that school board officers indicated “their desire for me to step away.” At the time, theschool board declined to address whether McKnight’s characterization of the meeting was accurate, sayingit was a personnel matter.

The fray came as the school system was the subject of county inspector general investigative inquiries related to its handling of sexual harassment and workplace bullying complaints filed about former middle school principal Joel Beidleman. The Washington Postrevealedin August that the school system hadreceived at least 18 written or verbal complaints about Beidleman dating back to 2016. Butlast yearhe was promoted to become principal of Paint Branch High School in Burtonsville. A subsequent investigation by Baltimore-based law firm Jackson Lewis unearthed more complaints, bringing the total to 25.

Many teachers said a principal sexually harassed them. He was promoted.

Beidleman has denied several of the allegations, and he was put on administrative leave in August amid The Post’s reporting. He has since leftthe school system.

In an interview last week, McKnight, who was joined by her attorney, vowed to defend her reputation and said the school board hadn’t conducted a fair process of evaluating her work.

“I love my job. I love supporting the children and families and staff and Montgomery County Public Schools,” she said on Jan. 23. “I think it’s not lost upon anyone that when you take on the superintendency at this point in time, particularly after the pandemic, you do it because you love it.”

McKnight’s attorney, Jason Downs, added that she was the first woman to serve as superintendent and she was being treated differently than her male predecessors who have “been allowed to finish their terms despite any high-profile incidents that may have been tried in the media.” Downs did notelaborate. However, in the past decade, former superintendent Joshua P. Starr abruptly ended his tenure in 2015 after questions about the direction of the district. Downs said McKnight was doing her job well and urged reporters to “look at those evaluations.” He did not respond to an inquiry about whether McKnight intended to release those evaluations.

Supporters of McKnight have come to her defense in recent weeks, includingshowing up to school board meeting sessions with signs pledging support. On Thursday, representatives from the county chapter of the NAACP, the Black Ministers Conference of Montgomery County and others penned a letter to school board members asking them to “rescind your request that Dr. McKnight step aside.”

“From the start she has been undermined by this Board and in the Beidleman case, not permitted to do her job,” the letter said. “In our view, the Board of Education is responsible for the six months of chaos and uncertainty that has accompanied this case.”

McKnight, who was named Montgomery superintendent in 2022 after previously serving as interim, has nearly two decades of experience with the school system. She was named Maryland Principal of the Year in 2015. Later, she briefly left the school system to join Howard County Public Schools, but returned to Montgomery County in 2019 to serve as deputy under Superintendent Jack R. Smith.

As deputy, sheled efforts to conduct an “anti-racist audit” to vet the district’s policies and curriculums. A 198-page reportreleased in 2022 foundthat students of color have a less satisfactory experience than White students in the school system. The audit said participants instakeholder group sessionsalso described a lack of coordination in the central office, skepticism that the school system would be honest about the results, and a “culture where there is a ‘cost’ to speaking up and power dynamics that stifle honest dialogue.”Share this articleNo subscription required to readShare

When Smith announced his retirementas superintendent in 2021, McKnight became the interim.

She led the school system as it was trying to return from winter break, while the omicron variant of the coronavirus was surging and shuttering schools. A nearby jurisdiction, Prince George’s County Public Schools, had announced it would delay an in-person reopening after the winter break. But McKnight’s administration committed to offering in-person learning with an option for schools to switch to virtual instructions if cases were too high. A color-coded chart with infection rates was unveiled that showed which schools were at risk of temporarily closing to mitigate the spread, but the plan was scrapped three days later after state objections. She apologized for the confusion in a community letter.

Shortly after, the Montgomery County Education Association — the teacher’s union — passed avote of no confidence in the school system’s leadership, includingMcKnight and theschool board. The resolution cited the lack of “a coherent plan” and a failure “to provide clear metrics and criteria” to guide decisions aboutschools reopening.

In early 2022, the district was reeling aftera student was shot at Magruder High School, sending the school on lockdown for hours. An amended after-action report sent to the statein 2023noted thatsome students were released into the hallwayafter the shooting and some staff were able to get inside the school despite it being on lockdown.

The tensions came as the school board was finalizing a search for a permanent superintendent.

In February 2022, a group of Black pastors wrote in a sharply worded letter that McKnight was being “strategically and unjustly vilified” during her candidacy to be superintendent. They accused several county officials of participating in a backdoor political effort to discredit McKnight.

Later that month, the school board unanimouslyapproved the hiring of McKnight as superintendent. At the time, then-school board president Brenda Wolff called the appointment historic. McKnightalso is the second African American to serve in the role. She started with a base salary of $320,000.

“It is emotional because I don’t take this responsibility lightly,” McKnightsaid after the 2022 vote. “I care for the children in the school system as I do for my own.”

As superintendent, her administration privately negotiated an agreement that brought community engagement officers back into schools, angering student activists and criminal justice advocates. She also oversaw the school system as it was dealing with an uptick in antisemitic incidents and calls from parents to provide an “opt-out” provision for books with LGBTQ+ characters.

In aletter tothe district Friday, McKnighttouted the school system’s progress in increasing early literacy and mathematics test scores since the return toin-person instruction. She also noted that under her tenure, an agreement with the schools’ unions led staff to receive a 7 percent salary increase at the beginning of the school yearwith anotherraise of at least 3 percent set for July.

The revelation of the Beidleman misconduct allegations sparked intensescrutiny of the district in recent months, including from the county council and the county’s inspector general.

Montgomery leaders upbraid MCPS for secrecy in principal allegations

County residents havequestioned how much McKnight knew about complaints involving Beidleman during his promotional process. At a MontgomeryCounty council oversight hearing in September, McKnight said, “I was not aware there was an internal investigation against Dr. Joel Beidleman at the time of his promotion.”

The county inspector general launched two inquiries into the school system. The first inquiry looked into all allegations of misconduct by Beidleman, and a report released in December found he violated the system’s sexual harassment and bullying policies.

The second inquiry scrutinized the school district’s general handling of misconduct complaints. A January report determined that school officials had been warned multiple times since 2019 about issues pertaining to the district’s processes for investigating employee reports of misconduct. But the school system didn’t take “any substantive action” to address those concerns, according to the report.

McKnightwas charged by the school board to implement a “corrective action plan.” In January, her administrationsaid the plan would, among other things,nix candidates for a promotion if they are under an active investigation and create more rigorous background check protocols.

The school system is expected to face another hearing in front of the county council’s audit, and education and culture committees on Feb. 8.

County Executive Marc Elrich (D) said during a news conference Friday that he still seeking answers from the school board about the situation. Those questions “have to be answered at some point,” he said.

He added that the school system’s policies around sexual harassment would need to change.

“I want to be clear,” he said, “Rebuilding trust is not going to be as simple as replacing the superintendent.”