By George F. Will Columnist|Follow authorFollow

Children are like trees, only more trouble. Winds that bend young trees expand the tree’s roots on the windward side, firmly anchoring the tree. And winds strengthen the wood on the other side by compressing its cellular structure. This growth dynamic, called “stress wood,” is a metaphor for the intelligent rearing of children, who need wind — the stresses of pressure and risk-taking — to become strong and rooted in the social soil.

Jonathan Haidt says a social catastrophe has resulted from the intersection of two recent phenomena. One is the “safetyism” of paranoid parenting, which injures bubble-wrapped children by excessively protecting them from exaggerated “stranger danger” and other irrational anxieties about the real world. The other is parental neglect regarding the “rewiring” of young brains by extreme immersion in the virtual world. This has been enabled by the swift, ubiquitous acquisition of smartphones, granting children something that is not, Haidt argues, age-appropriate: unrestricted access to the internet.

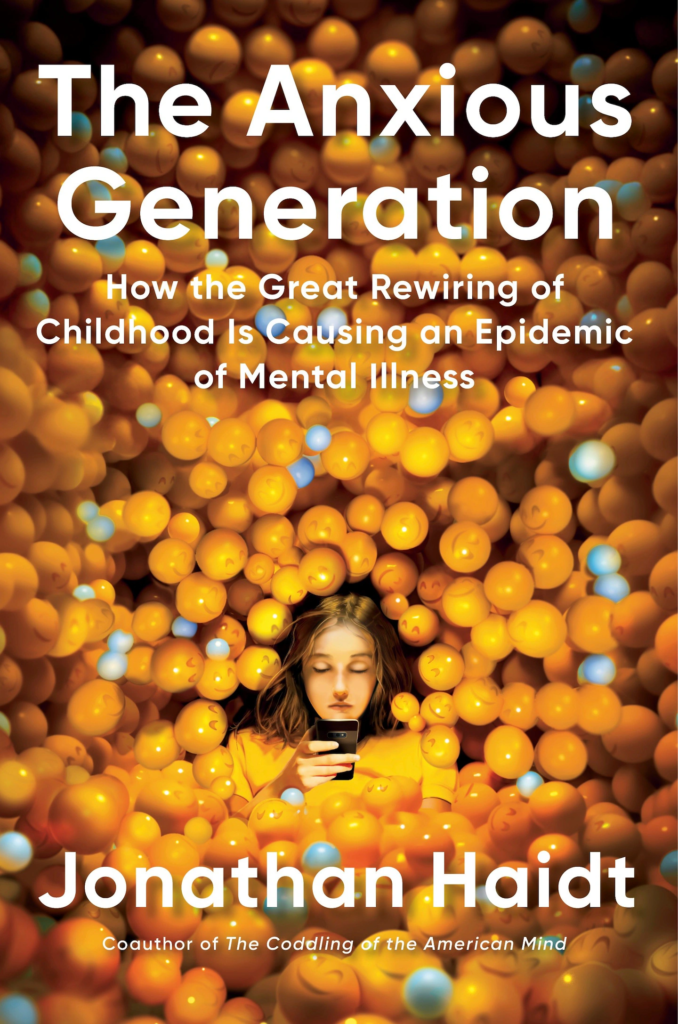

With his just-published “The Anxious Generation,” Haidt hopes to demonstrate that Johannes Gutenberg’s legacy — movable type, mass literacy: books — still matters more than Steve Jobs’s devices. Haidt, a New York University social psychologist, encourages dismay about what has happened since, around 2010, smartphones became common accoutrements of children at vulnerable developmental ages. Haidt: “Children’s brains grow to 90 percent of full size by age five, but then take a long time to wire up and configure themselves.”

High-speed broadband arrived in the early 2000s; the iPhone debuted in 2007. Since about 2010, social media companies have designed “a firehose of addictive content” for Gen Zers (born after 1995) who are often socially insecure, swayed by peer pressure and hungry for social validation. Gen Z became the first generation “to go through puberty with a portal in their pockets that called them away from the people nearby and into an alternative universe.”

Phone-based childhood displaced play-based childhood and its unsupervised conversing, touching and negotiating the small-scale frictions and setbacks that prepare children for adulthood. Fearful parents, convinced the real world is comprehensively menacing (and worried about overbroad “child endangerment” laws), will not allow their children to walk alone to a nearby store. But they allow their children unrestricted wallowing in the internet, especially social media.

The results, Haidt says — sleep deprivation, socialization deprivation, attention fragmentation — produced “failure-to-launch” boys living protractedly with parents, and girls depressed by visual social comparisons and perfectionism. Soon, college campuses were awash with timid, bewildered late-adolescents. After their phone-based childhoods (Haidt calls social media “the most efficient conformity engines ever invented”), they begged for “safe spaces” to protect their fragile “emotional safety.”

Haidt recommends “more unsupervised play and childhood independence,” “no smartphones before high school” and “no social media before 16.” There is, however, a “collective action” problem: It is difficult for a few scattered parents to resist the new technology’s tidal pull on most of their children’s peers.

Techno-pessimists should avoid the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy: The rooster crows, then the sun rises, so the crowing caused the sunrise. If smartphones vanished, schoolchildren would still be spoon-fed anxiety and depression about (if they are White) their complicity in their rotten country’s systemic racism, and (if they are not White) their grinding victimhood, until we all perish from climate change.

Haidt’s data demonstrating a correlation (the arrivals of smartphones and of increased mental disorders) suggest causation, but remember: Moral panics about new cultural phenomena — from automobiles (sex in the back seats) to comic books (really) to television to video games to the internet — are features of this excitable age.

Although Haidt is always humane and mostly convincing, his argument does not constitute a case for government trying to do what parents and schools can do. They can emulate Shane Voss.

In Durango, a city in southwest Colorado, Voss, head of Mountain Middle School, acted early, and decisively. In 2012, he banned access to smartphones during the school day. The results, Haidt writes, were “transformative”:

“Students no longer sat next to each other, scrolling while waiting for homeroom or class to start. They talked to each other or the teacher. Voss says that when he walks into a school without a phone ban, ‘It’s kind of like the zombie apocalypse and you have all these kids on the hallways not talking to each other.’”

Soon Voss’s school reached Colorado’s highest academic rating. This local experience constitutes a recommendation to the nation. Recognize the potentially constructive power of negation: Just say no.

Opinion by George F. WillGeorge F. Will writes a twice-weekly column on politics and domestic and foreign affairs. He began his column with The Post in 1974, and he received the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1977. His latest book, “American Happiness and Discontents,” was released in September 2021. Twitter

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/04/05/jonathan-haidt-anxious-generation-solutions/