Maryland lawmakers prioritized the alternative disciplinary practice four years ago, but the rollout has been complicated

By Caralee AdamsJuly 15, 2023 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

The skirmish last fall began on a Montgomery County school bus.

Someone — no one is sure who — tossed a water bottle from the back of the bus, smacking a sixth-grader sitting near the front. The next day, the victim retaliated by throwing a container of milk to the back, dousing a seventh-grader.F

The two girls, who live near each other, were headed for a fight — and possibly suspension. But their parents called the school for help, and one of the Montgomery County Public Schools’ newly appointed instructional specialists in restorative justice got to work.

With permission from the families, Floyd Branch III, the specialist, brought the girls together for lunch and a “restorative circle” to defuse the tension. Neither of the girls really wanted to target the other, but they were embarrassed by the incident and by students laughing at them on the bus.

“They were able to talk it out and say they were sorry,” Branch said. “Children can’t learn if they don’t understand what the mistake was, or when there’s no conversation.” The process did not turn the two into friends, he said, but they have been able to ride the bus together without any more fighting.

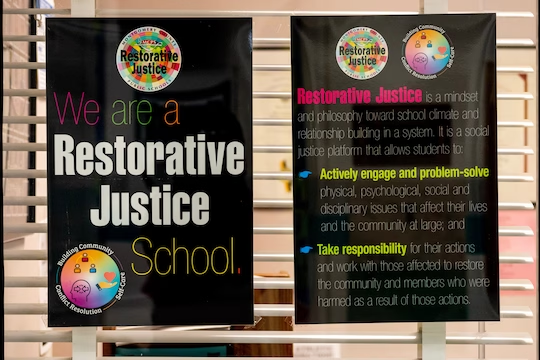

This situation, and its resolution, is a good example of restorative justice at work, say supporters of this approach to discipline and community building. Instead of focusing on punishment, restorative practices invite those in conflict to talk through the issue so they can understand the harm caused, take responsibility and find ways to move forward.

Elements of restorative justice have long been used in Indigenous cultures, and, since the 1970s, as part of alternative sentencing programs in the criminal justice system. The practice spread to schools in the 1990s and accelerated after 2014 as an alternative to “zero-tolerance” suspension and expulsion policies for misbehavior. Those consequences, experts say, are fraught with problems. Exclusionary discipline doesn’t serve as a deterrent and often derails a student’s educational path: Black students, boys, and students with disabilities are more likely to be suspended and expelled than other students, and school administrators often discipline Black students more severely and frequently than White students who engage in the same behaviors.

In 2019, Maryland legislators passed a law requiring districts to incorporate restorative approaches in their discipline policies. Montgomery County, which is the largest school district in Maryland, with more than 160,000 students, has leaned into the practice, adding staff whose job is to help to build and repair relationships among all members of a school community — students, teachers, parents and administrators. There are still suspensions for serious offenses, according to the system’s code of conduct, but restorative justice is among the discipline that schools can use.

Shauna-Kay Jorandby, who oversees school engagement, behavioral health and academics for the district, said that based on the results of a recent survey, students are looking for the support that restorative justice promises.

“We know that our kids need help communicating, talking and understanding each other,” Jorandby said. “We know that they need help with conflict, whether it’s at school or at home. We know they need help with the stressors in their life.”

Opinion: Don’t fret over antisemitism in schools. We have restorative circles.

But the school system’s efforts are coming at a time when there’s been a call among some for stronger penalties for acting out in schools, in response to higher misbehavior rates after students returned from pandemic shutdowns. In some districts, police, who were banned from campuses in 2020, have been asked to return.

In Montgomery County, some parents, teachers and students have pushed back against restorative justice, saying harsher discipline is sometimes necessary to hold students accountable. Others question the way restorative circles are conducted, noting that the circles are often led by staff from the district’s central office, who the students don’t know or trust. They want to see more training, consistency and transparency about the process.

The new approach to student behavior is leading to a “free for all” in the schools; kids are getting away with hurting one another, said Ricky Ribeiro, a parent and PTA vice president at John F. Kennedy High School in Silver Spring. He wants the district to explain why the restorative approach is better than what’s been used in the past and provide evidence.

“Implementing this system is not going to be easy. It’s unclear if it will be successful, if we even know what success looks like, and if we have enough resources to make it successful,” Ribeiro said. “And yet, MCPS is going all-in with the kitchen sink on it, and I don’t know [if] that’s a good idea.”

The district’s restorative justice work was put to the test earlier this year after an antisemitic incident roiled a high school.

The school system is coping with a spate of hate, bias and racist incidents — an average of one per day, which is three times higher than previous years, Superintendent Monifa McKnight told the community in an address April 27. Last December, two students on the school debate team at Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda allegedly made antisemitic comments about their Jewish teammates on an off-campus trip.

The offenders were disciplined by the school, and the district brought in restorative justice specialists to hold sessions with students. Rachel Barold, who was a ninth-grader at the time of the incident, said she felt the process didn’t work in that situation and let the offenders off too easily.

“Restorative justice circles are great for maybe bullying or other offenses at MCPS, but acts of hate against a group of people based on the ethnicity or religion — that is not the place,” said Barold, who is Jewish. “Restorative justice is a lot about forgiving who did it. And having to sit in the same room with them. It’s really re-traumatizing victims.”

Restorative justice sessions are voluntary, though Barold said she and other members of the debate team felt pressure to participate. Going into the restorative circles, students didn’t know the district specialists leading the conversation or what to expect, she said. For example, some students had prepared remarks saved on their cellphones, but were told cellphones weren’t allowed. Afterward, school administrators acknowledged they had made mistakes. Barold hopes the district will use the feedback to modify a process that she felt favored the offenders over the victims.

The school’s principal, Robert Dodd, did not respond to three interview requests. Whitman’s school paper, The Black and White, reported that the students received a month-long suspension from the debate team.

Jorandby said restorative conversations don’t take away the hurt, but they can be a first step to healing, even with hate and bias. The district has developed a consent and feedback form for formal restorative conferences emphasizing that the process is voluntary and gives parents the opportunity to decline consent for their child to participate.

OPINION: Restorative justice isn’t a panacea, but it can promote better relationships among students

The official consent form is among the ways district officials say they are trying to make the restorative justice program more robust. Last school year, the district hired six restorative justice specialists in the district’s central office, bringing the total to nine. Each specialist is assigned to serve a cluster of schools. The district is also paying a stipend to a staff member in each school to act as a restorative justice coach. All staff are required to take a short restorative justice training session and administrators have been asked to consider restorative approaches when crafting new goals for school climate, culture and student well-being in school improvement plans.

“It’s a work in progress,” said Damon Monteleone, an associate superintendent in the office of school support and well-being for Montgomery County schools. The district’s own data shows this: Nearly three-quarters of school leaders who participated in a self-evaluation released in May said they were either early in their development of restorative justice processes or had no processes in place at all. Only 3 percent believed they had a “mature” process in place.

That is not surprising. With the pandemic and its ensuing disruption of in-person learning, 2022-23 was the first normal school year for restorative justice in the schools since the 2019 state policy change, Monteleone said. The district itself is still learning what works, but it’s not ignoring criticism, he said.

It can take time for restorative justice to take hold in a school’s culture — as much as three to five years, say experts — and, as with any major shift, the process can be controversial. But research consistently shows the approach has a positive effect on students. A recent report by Sean Darling-Hammond, assistant professor of health and education at UCLA, indicates that restorative practices improve middle school students’ academic achievement, while reducing suspension rates and disparities, misbehavior, substance abuse and student mental health challenges.

Opinion: When students stumble, colleges should turn to restorative justice before expulsion

Such work also needs money. The Maryland law, while well-intentioned, isn’t adequately funded, said David Hornbeck, a former Maryland state schools superintendent. In March, he launched Restorative Schools Maryland, a nonprofit that advocates for restorative justice policies and funding.

Rather than a few people from a district’s central office being called to put out fires, the work of restorative practices requires full-time staff in the schools, Hornbeck said.

“We face a challenge in people thinking that restorative practice is a kind of touchy-feely, namby-pamby, let-the-kids-off-the-hook thing — and that couldn’t be further from truth,” he said. Hornbeck said he also wants schools to track suspensions, teacher turnover, and student absenteeism to make sure their restorative justice practices actually work.

For this approach to work, supporters say, it will require investment on the front end. In Montgomery County schools, officials say about 80 percent of the restorative justice work is preventive (holding “community circles,” promoting self-care, teaching conflict resolution strategies) and 20 percent is responsive (repair practices and restorative conferences).

Daphne McKay, who retired at the end of the year as a restorative justice coach at Kingsview Middle School in Germantown, said the circles give students space to process experiences and create a sense of belonging.

“The more people we have in our lives supporting us, the better,” she said. “Restorative justice is all about sitting down and hearing one another’s perspectives and trying to find a way to come together and understand one another.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2023/07/15/restorative-justice-montgomery-county-schools/

This report about restorative justice in the classroom was produced by The Hechinger Report [hechingerreport.org], a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.