By Britt Peterson WP June 16 2023 Magazine

Ayobami Balogun, 23, thought she would work at Microsoft for the rest of her life.

As an immigrant from Nigeria and the oldest of five children, she had chosen a career in software engineering because it would provide financial stability and manageable hours. Growing up, Balogun had watched her parents work multiple jobs as home aides for people living with special needs while she helped take care of her siblings. After several internships while she was a student at Ohio State University, Balogun accepted a full-time job in 2020 upon graduating.

Everything seemed to be falling into place — until March, when she lost her job in companywide layoffs.

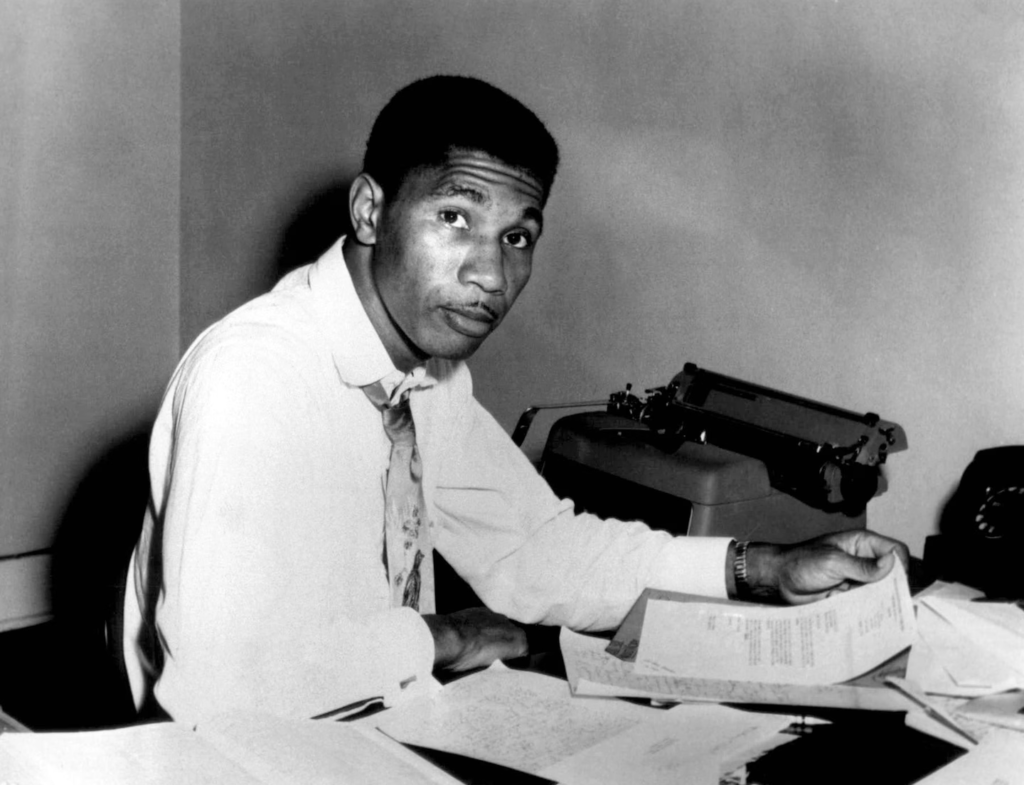

Balogun was not too worried, however. Along with her severance package from Microsoft, she already had two side hustles — an Airbnb business and an events company called BeBs that she runs with her best friend. Being laid off also gave her the chance to think about what she really wants in her career — the first time she has had time to do so. “I don’t want to be the only Black person or the only woman on my team,” she said, explaining that she is looking more intently at a company’s values, particularly when it comes to diversity, equity and inclusion, during her job search. “I feel like that’s scary.”

Balogun works from home managing her businesses to supplement her income after being let go from Microsoft. (Megan Jelinger for The Washington Post)

Balogun’s resilient self-confidence and determination are common traits for Gen Z — often defined as people born between 1997-2012 — who have begun entering the workforce. They are more diverse, tolerant, educated and socially committed than past generations, yet they also report higher levels of stress, mental illness and poverty. And as one of the largest generations — they make up one-fourth of the U.S. population — they have tremendous potential to transform not just the job hunt process but also the industries they’re entering.

“I would like to be able to afford some things, but I don’t want to be attached to the material grind,” said Griffon Hooper, a University of San Diego graduate who is working at a dive shop while applying for jobs in his chosen field: nautical archaeology. “I’m not interested in sacrificing 30 years of my life for a handshake and a golden watch. And I don’t think a lot of people are anymore.”

“What Gen Z wants is to do meaningful work with a sense of autonomy and flexibility and work-life balance and work with people who work collaboratively,” said Julie Lee, director of technology and mental health at Harvard Alumni for Mental Health, and an expert on Gen Z health and employment. Gen Z is less afraid to ask for the things that everyone else really wants and needs, which sometimes is stereotyped at work as being entitled and narcissistic.

“During the time I entered the workforce, I didn’t feel empowered,” Lee said. “I didn’t feel that I was able to ask for those things.”

Workplaces seem to be listening. According to several recruiters and hiring managers from companies on the Top Workplaces list, Gen Z is making an impact on the way they conduct their jobs and on their office culture, from the significant to the small-bore.

Griffon Hooper, a University of San Diego graduate, is working at a dive shop while applying for jobs in nautical archaeology. (Sandy Huffaker for The Washington Post)

“We started the Gen Z word of the week,” said Suzanne Hawes, chief human resources officer at the intellectual-property law firm Sterne Kessler, who says 4 of her 14-person team are Gen Z. “Every week they’ll present something to me and see if I already know it, and if I don’t already know it they’ll explain it to me … and they give me huge kudos when I can use it in a sentence.”

So far the words have included the fire emoji and the term “clout.” Hawes said: “I was like, I know what ‘clout’ is! But it’s all these new interpretations.”

Gen Z has been indelibly molded by continuous political and economic upheavals. Many of them grew up in the aftermath of the attack on the World Trade Center in New York City that led to wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, followed by the Great Recession, a global pandemic, demonstrations about racial issues and a governmental insurrection, to name a few. Maintaining trust in authority and the institutions meant to manage society, as a result, can be tough.

“There’s this feeling of betrayal,” admits Kevin Lu, 23, who wants to work in the burgeoning field of climate technology. “I feel like so many times continuously throughout this generation’s life, they are promised a certain thing only to get it detoured or pushed back.”

Jordan McCullar, center, works at a computer at Hager Sharp in D.C. (Tom Brenner for The Washington Post)

Billie Gardner, 24, has already experienced these upheavals personally. During her senior year in college, she won a competitive fellowship to work on Joe Biden’s presidential campaign only for a pandemic to squander all plans and her job. She moved back home to Idaho and worked at a Lululemon while she searched for a new job and socialized with friends via Zoom.

In early 2021, after applying to different positions for months, Gardner got another fellowship and moved to D.C., where she continued to work nights and weekends at a Lululemon outlet to support herself; toward the end, she was hired by a nonprofit organization called Represent Us. The job paid well, and Gardner loved the work, but when donor networks shriveled during the pandemic she lost her job, again. “I had no idea what I was going to do,” she said. “I was calling my parents. … I was like, ‘Mom, do I sell this couch I just bought?’”

And yet, despite all the ups and downs, Gardner remains focused on finding a job that aligned with her values, and where she would feel welcome and supported. “What’s important for me is that not only am I a fit for the job, but is the job a fit for me,” she said. In interviews, she paid attention to who was in the room — how many women, how many people of color — as a clue for the company’s actual commitment to diversity. “The makeup of the organization is important to me almost as much as the work I’m going to be doing,” she said.

Jenny Fernandez, a professor at Columbia Business School and an executive coach who frequently works with Gen Z leaders, described the generation as both realistic and idealistic. “They’re not willing to compromise [on job security], they want to be paid,” she said. “At the same time, they have options, and they know they have options.”

Christopher Barnes works as his dog Leo hangs out in his cubicle at the SCLogic in Annapolis, Md. (Amanda Andrade-Rhoades for The Washington Post)

Despite the severe loss of jobs during the pandemic, Gen Z actually has more opportunities than any group of recent graduates going back to before the Great Recession. Companies are often competing for them, instead of the other way around, and that, combined with the exigencies of the time they were born into, lends a certain empowerment. As Bianca Alvarado, a 23-year-old junior publicist at a marketing firm in Los Angeles who spent months looking for a job after graduation, said: “People my age don’t take any bulls—. … We’re doing our best to rise above all the mistakes of past generations and fix things more urgently.”

During the job-application process, Gen Z has the digital tools to research companies on a level previous generations couldn’t. Alvarado recalled watching a TikTok video on job interviews that instructed her to always have a question ready. Once hired, they are activists. A majority of them view capitalism in a negative light, but they’re actively working to improve the system. More pro-labor than past generations, Gen Zers are leading union drives and making educational TikToks about unfair labor practices.

They are also focused on more collective and holistic notions of stability: How can our jobs and careers help build long-term security for our communities, the world around us and our lives outside the workplace? Several people interviewed for this story emphasized the importance of working for companies invested in environmental sustainability — in other words, contributing to planetary stability. “I’m not going to work for a company that might be harming the climate in a very obvious way,” said Balogun, echoing the 67 percent of Gen Zers who believe that the climate should be a top priority, according to a 2021 Pew Research Center survey.

Forbright Bank, a Chevy Chase-based full-service bank with a stated mission to “accelerate the transition to a sustainable and clean energy economy” and a slew of employee incentives for climate-friendly choices like riding a bike to work and using solar electricity at home, would appear to be the kind of workplace that would draw Gen Z talent — and that does seem to be the case. Out of 180 new employees the bank hired last year, 40 were Gen Z, according to Randi Killen, executive vice president of human resources. “The Gen Zers really get excited about the possibility to work for a company that aligns with their values,” Killen said.

Gen Z also reports new interest in jobs that contribute to one’s personal stability, both mental and physical. Emma Choi, 23, who lost her podcast hosting job in the recent layoffs at NPR only to be quickly rehired as a producer for the NPR show “Wait, Wait … Don’t Tell Me!,” had always wanted to be an English teacher until continuous school shootings dissuaded her. “There’s already so many factors to put into what you want to do and where you want to work — now you have to put in your personal safety, too,” she said.

Emma Choi had wanted to be an English teacher, but school shootings dissuaded her. (Sophie Park for The Washington Post)

Mental safety is also a major priority. Gen Zers have higher reported rates of mental illness than previous generations, and youth suicide rates have shot up over the past decade — and all of that was even before the pandemic, which doubled anxiety and depression symptoms among young people globally, according to a 2021 study published in JAMA.

Young people, aware of the potential consequences of overwork and burnout, are making very different choices than past generations when it comes to work-life balance. Jillian Fan, 22, earned a degree in science, tech and international affairs with a minor in math from Georgetown University in 2022. The isolation of a pandemic and the relentless pressure at school contributed to a burnout so severe she moved back home to Reston, Va., for nine months, visiting family in Taiwan, baking and attending therapy sessions.

Initially, Fan, who felt “incredibly privileged” to be able to take the time off without immediate financial pressure, applied to jobs in her major, but her dream of going to culinary school lingered. “I’ve already spent six months doing nothing and the world hasn’t ended, can I perhaps do the wrong thing? I can make … mistakes,” she realized. She began casting a wider net in her job search and now works three part-time jobs, one at a bakery and two at local food-justice nonprofit groups, all work she loves and can imagine doing for the rest of her life.

Jillian Fan earned a degree in science, tech and international affairs with a minor in math from Georgetown. (Amanda Andrade-Rhoades for The Washington Post)

Although Gen Z has only been in the workplace for a couple of years, work is already changing in response to their new demands. In studies, Gen Z tends to be split when it comes to remote work: Some appreciate the flexibility and lack of a commute, while others, having already spent years at home in tiny apartments and group homes or with their parents, are very ready to return. “For the past three years, my entire life was virtual,” said Gardner who recently started a new job as a government relations associate at the Council on Foundations in D.C. When they offered her the choice between working fully remote or hybrid. “I was like, hybrid, please!”

Jordana Coppola, the chief people officer at OTJ Architects, a D.C.-based firm, said that her office now works to be sensitive both to people who need to stay home and people who want to come in. “You have these students that maybe have recently graduated and they moved to D.C. to take this job, and they’re in their apartment by themselves,” she said. “And they’re lonely. … We really work hard to make them feel connected.”

Gen Z’s need for meaningful work has also required some offices to be more transparent about the purpose of what they’re asking their more junior employees to do, as well as providing clear pathways to advancement. “The other thing that Gen Z is looking for … is what your organization can offer them as far as growth and development. What are the mentorship opportunities going to be, what kind of professional development is going to be available for them,” said Erin Federle, vice president of human resources at Decision Lens, a software company headquartered in Arlington. Because the company is small, it has a harder time creating internal job-training programs — so instead, they’ve begun paying for employees to take courses outside the company, as well as focusing on building internal mentoring relationships.

Suzanne Hawes works at a computer while meeting with some Gen Z members of the team at Sterne Kessler. (Andre Chung for The Washington Post)

Recruiters also described a new need to be direct about a company’s values and even politics — not just in the workplace generally but starting at the interview stage. “[Younger job-interview subjects] will ask about what kind of initiatives the firm is doing to increase representation and inclusion,” said Hawes, of Sterne Kessler. All the companies interviewed for this story insisted that diversity, equity and inclusion, as well as environmental sustainability, had been priorities before Gen Z started demanding them. But it’s clear that at least when it comes to selling their values, companies are held to a higher standard now than ever before.

“I just feel like this generation is going to make huge strides for the workplace,” Hawes added. “They’re not afraid to ask for what they need and want. … They’re pushing for impressive changes, things that, as a Gen Xer, I didn’t think were possible. So I’m absolutely here for it, as they would say.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/06/16/gen-z-employment/