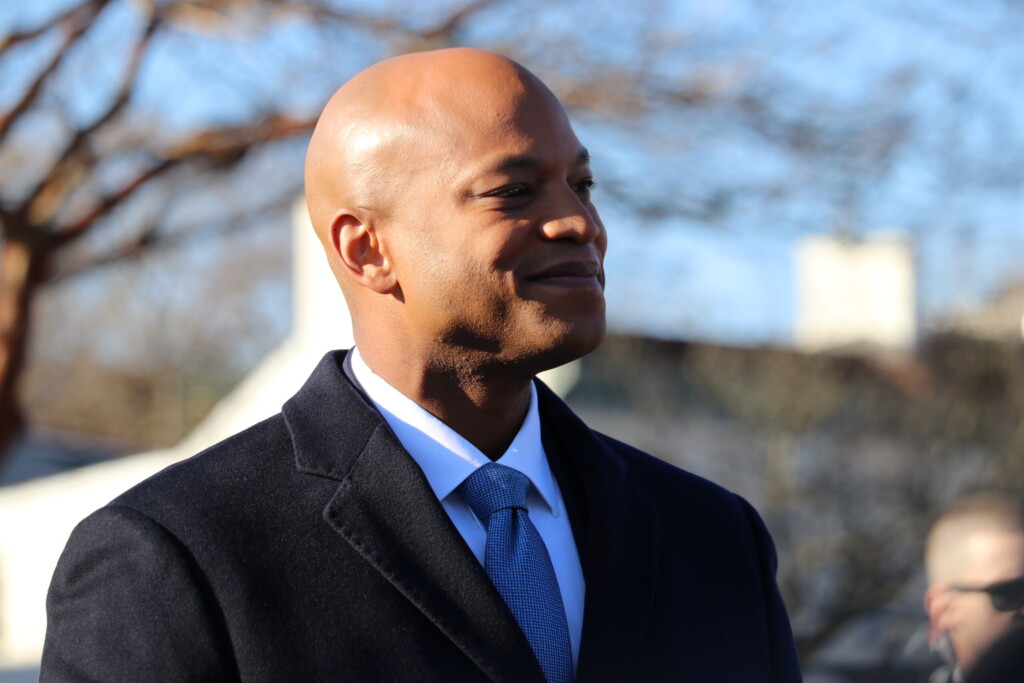

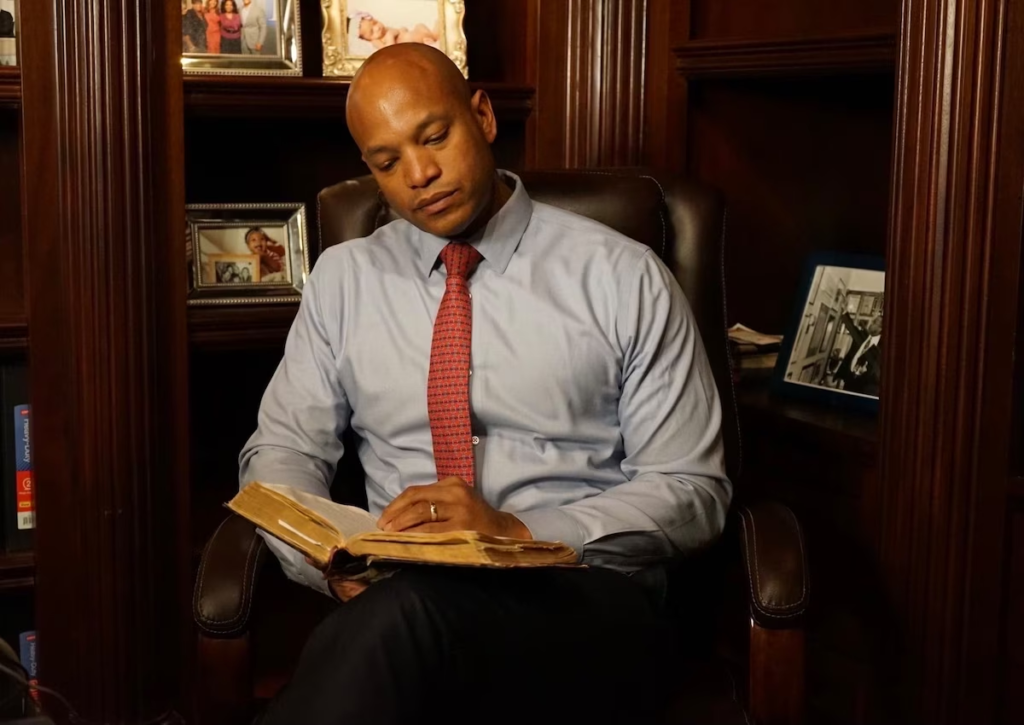

Gov. Wes Moore was sworn in as Maryland’s 63rd governor and first Black executive shortly after noon on Wednesday. These are his remarks, as prepared before the ceremony, though the newly minted governor took liberty to ad-lib during his first address.

Good morning, Maryland, and from the bottom of my heart, thank you for the honor you have bestowed upon me and Aruna.

President Ferguson, Speaker Jones, and Members of the Maryland General Assembly, thank you, all. It’s an honor to be your partner.

To all the state workers, and all who organized this inauguration, thank you. It’s an honor to be your colleague.

And to Governor Hogan: We are grateful for the kindness you, and your team, have shown throughout this transition. Thank you for your eight years of service to the state we both love.

To my friend Oprah Winfrey — a Maryland girl at heart — thank you for your gracious and generous introduction. And thank you for always being in my corner.

To my wife, Dawn, our daughter, Mia, and our son, James, you are my heart, my soul, and my everything.

As I stand here today, looking out over Lawyers’ Mall, at the memorial to Justice Thurgood Marshall, it’s impossible not to think about our past and our path.

We are blocks away from the Annapolis docks, where so many enslaved people arrived in this country against their will. And we are standing in front of a capitol building built by their hands.

We have made uneven and unimaginable progress since then. It is a history created by generations of people whose own history was lost, stolen, or never recorded. And it is a shared history – our history – made by people who, over the last two centuries, regardless of their origin story to Maryland, fought to build a state, and a country, that works for everybody.

There are two people who embody that spirit sitting right here, in the front row. Two extraordinary women named Hema and Joy.

Hema came to this country from India; Joy from Jamaica. They immigrated to America with hope in their hearts, not just for themselves, but for future generations.

Today, they are sitting here at the inauguration of their children as the Governor and Lieutenant Governor of the state that helped to welcome them.

To Aruna’s mother, Hema… and to my mom, Joy… you epitomize everything special about this state; You are proof that in Maryland, anything is possible.

Now yes, Aruna’s and my portraits are going to look a little different from the ones we’ve always seen in the capitol. But that’s not the point. This journey has never been about “making history.” It is about marching forward.

Today is not an indictment of the past; it’s a celebration of our future.

And today is our opportunity to begin a future so bright, it is blinding.

But only if we are intentional, inclusive, and disciplined in confronting challenges, making hard choices, and seizing the opportunity in front of us.

Our state is truly remarkable. From my birthplace of Montgomery County… to my adoptive home of Baltimore City…From the sandy beaches of the Eastern Shore… to the rolling hills of Western Maryland… and everywhere in between.

Maryland is home to spectacular natural beauty, dynamic industries, and people as talented as they are determined.

But…the truth is: Maryland is asset-rich and strategy-poor.

And for too long, we have left too many people behind.

We know it is unacceptable that while Maryland has the highest median income in the country, one in eight of our children lives in poverty.

We know it is unacceptable that in the home of some of the best medical institutions on the planet, that more than 250,000 Marylanders lack healthcare coverage.

We’ve been asked to accept that some of us must be left behind. That in order for some to win, others must lose.

And not only that: We have come to expect that the people who have always lost… will keep losing.

Well, we must refuse to accept that.

Instead, I am asking you to believe that Maryland can be different.

That Maryland can be bold.

That Maryland can lead.

It is time for our policies to be as bold as our aspirations—and to confront the fact that we have been offered false choices.

We do not have to choose between a competitive economy and an equitable one.

Maryland should not be 43rd in unemployment, or 44th in the cost of doing business.

We should not tolerate an 8-to-1 racial wealth gap, not because it hurts certain groups, but because it prevents all of us from reaching our full potential.

We can attract and retain top industries, like aerospace, clean energy, and cybersecurity… and raise our minimum wage to $15 an hour to help folks feed their families.

Maryland can reward entrepreneurs who take bold risks… and provide stability for families in need.

This can be the best state in America to be an employer and an employee.

It shouldn’t be a choice — and it isn’t a choice. The path forward requires us to do these things together.

Now, here’s another false choice we often hear: That people must choose between feeling safe in their own communities, and feeling safe in their own skin.

Over the last eight years, the rate of violent crime has risen. Many Marylanders have grown weary in their faith in government’s ability to keep them safe.

We can build a police force that moves with appropriate intensity and absolute integrity and full accountability, and embrace the fact that we can’t militarize ourselves to safety.

We can support our first responders who risk everything to protect us, and change the inexcusable fact that Maryland incarcerates more Black boys than any other state.

We will work with communities from West Baltimore to Westminster to share data so we can keep violent offenders off our streets. And we can welcome people who have earned a second chance back to our communities.

I know what it feels like to have handcuffs on my wrists. It happened to me when I was 11 years old. I also know what it’s like to mourn the victims of violent crime.

We do not have to choose between a safe state and a just state. Maryland can, and will, be both.

We are often told climate change is a problem for the future, or something you only have to worry about if you live on farmland or in a flood zone.

But climate change is an existential threat for our entire state, and it is happening now.

Confronting climate change represents another chance for Maryland to lead. We can be a leader in wind technology, in grid electrification, and clean transit.

We will protect our Chesapeake Bay, and address the toxic air pollution that chokes our cities. And we will put Maryland on track to generate 100 percent clean energy by 2035 — creating thousands of jobs in the process.

Clean energy will not just be part of our economy; clean energy will define our economy.

This requires everyone — companies, communities, state and local governments, and the people — to take bold and decisive action, together.

And importantly, we do not have to choose between giving our children an excellent education and an equitable one.

We will ensure that every student knows their state loves, and needs them — and we will create policies to help them thrive.

We will invest in our special education students, our English language learners, our LGBTQIA+ students, students experiencing homelessness, and every kid who needs a little extra help.

We will see to it that mental and behavioral health challenges do not prevent our children from getting the education they need and deserve.

And while Maryland is home to some of the world’s greatest institutions of higher education — a fact of which we should be very proud — we must end the myth that young people must attend one of them to be successful.

Every student in Maryland will know that there are many paths to success and fulfillment — and those paths begin with high-quality, highly inclusive schools from Pre-K to 12th grade.

My own journey started in military school, where I learned one of my core values: Service. I went on to lead soldiers in Afghanistan.

My years of service transformed me. My character was strengthened, my vistas were widened, my leadership was tested.

I want every young Marylander, of every background, in every community, to have the opportunity to serve our state. That is why we will offer a service year option for all high school graduates.

A year of service will prepare young people for their careers — and provide our state with future leaders: public servants we desperately need.

The challenges we face will require us to answer the call of service. To join the ranks of our teachers and our firefighters, our police officers and our civil servants, our nurses, and union members.

You’ve elected me to serve as your Governor, but the work, will be done together. Now there will be skeptics, who will say that we cannot rise above the toxic partisanship we see all too often in today’s politics, where people care more about where the idea came from than is it a good idea. Those voices told me at the beginning of my campaign, “You don’t understand how politics works.” To them I said and I say, “We must govern on big principles instead of petty differences.”

To them I said and I say, we must form broad coalitions that bring people together rather than scare them. I said and I say, the urgency of the moment demands a different way of serving the people.

While I led paratroopers, do you know what question I never asked my soldiers, what’s your political party?

I will govern the same way: For all Marylanders. For those who did not vote for me, I will work to earn your support; for those who did, I will work to keep it.

Now, to work together, it means we must also get to know each other again. To come together across lines of difference –– both real and perceived –– to build uncommon coalitions.

Because the simple fact is we need each other; we all have a role to play.

And that’s the lesson from generations before us. We are being called on to come together so we can march forward.

“And let us march on til victory is won.“

But understanding that today is not the victory –– today is the opportunity.

An opportunity to lead with love. An opportunity To create with compassion. An opportunity To fight fearlessly for our future.

Maryland: our time is now. Our time is now to build a state that those who came before us fought for, a state that leaves no one behind.

That is not a slogan; it is a fulfillment of a hope.

It’s our time, Maryland. Let’s lead.

Thank you.

https://www.marylandmatters.org/2023/01/18/read-gov-wes-moores-prepared-remarks-upon-his-inauguration-as-the-63rd-governor-of-maryland/