Science suggests we’re hardwired to delude ourselves. Can we do anything about it?By Ben Yagoda SEPTEMBER 2018 The Atlantic

I am staring at a photograph of myself that shows me 20 years older than I am now. I have not stepped into the twilight zone. Rather, I am trying to rid myself of some measure of my present bias, which is the tendency people have, when considering a trade-off between two future moments, to more heavily weight the one closer to the present. A great many academic studies have shown this bias—also known as hyperbolic discounting—to be robust and persistent.

Discover “Where Memories Live”

In the second chapter of “Inheritance,” The Atlantic explores how place informs history—and how history shapes who we are.Explore

Most of them have focused on money. When asked whether they would prefer to have, say, $150 today or $180 in one month, people tend to choose the $150. Giving up a 20 percent return on investment is a bad move—which is easy to recognize when the question is thrust away from the present. Asked whether they would take $150 a year from now or $180 in 13 months, people are overwhelmingly willing to wait an extra month for the extra $30.

Present bias shows up not just in experiments, of course, but in the real world. Especially in the United States, people egregiously undersave for retirement—even when they make enough money to not spend their whole paycheck on expenses, and even when they work for a company that will kick in additional funds to retirement plans when they contribute.

That state of affairs led a scholar named Hal Hershfield to play around with photographs. Hershfield is a marketing professor at UCLA whose research starts from the idea that people are “estranged” from their future self. As a result, he explained in a 2011 paper, “saving is like a choice between spending money today or giving it to a stranger years from now.” The paper described an attempt by Hershfield and several colleagues to modify that state of mind in their students. They had the students observe, for a minute or so, virtual-reality avatars showing what they would look like at age 70. Then they asked the students what they would do if they unexpectedly came into $1,000. The students who had looked their older self in the eye said they would put an average of $172 into a retirement account. That’s more than double the amount that would have been invested by members of the control group, who were willing to sock away an average of only $80.

I am already old—in my early 60s, if you must know—so Hershfield furnished me not only with an image of myself in my 80s (complete with age spots, an exorbitantly asymmetrical face, and wrinkles as deep as a Manhattan pothole) but also with an image of my daughter as she’ll look decades from now. What this did, he explained, was make me ask myself, How will I feel toward the end of my life if my offspring are not taken care of?

When people hear the word bias, many if not most will think of either racial prejudice or news organizations that slant their coverage to favor one political position over another. Present bias, by contrast, is an example of cognitive bias—the collection of faulty ways of thinking that is apparently hardwired into the human brain. The collection is large. Wikipedia’s “List of cognitive biases” contains 185 entries, from actor-observer bias (“the tendency for explanations of other individuals’ behaviors to overemphasize the influence of their personality and underemphasize the influence of their situation … and for explanations of one’s own behaviors to do the opposite”) to the Zeigarnik effect (“uncompleted or interrupted tasks are remembered better than completed ones”).

Some of the 185 are dubious or trivial. The ikea effect, for instance, is defined as “the tendency for people to place a disproportionately high value on objects that they partially assembled themselves.” And others closely resemble one another to the point of redundancy. But a solid group of 100 or so biases has been repeatedly shown to exist, and can make a hash of our lives.

FROM OUR SEPTEMBER 2018 ISSUE

Check out the full table of contents and find your next story to read.See More

The gambler’s fallacy makes us absolutely certain that, if a coin has landed heads up five times in a row, it’s more likely to land tails up the sixth time. In fact, the odds are still 50-50. Optimism bias leads us to consistently underestimate the costs and the duration of basically every project we undertake. Availability bias makes us think that, say, traveling by plane is more dangerous than traveling by car. (Images of plane crashes are more vivid and dramatic in our memory and imagination, and hence more available to our consciousness.)

The anchoring effect is our tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered, particularly if that information is presented in numeric form, when making decisions, estimates, or predictions. This is the reason negotiators start with a number that is deliberately too low or too high: They know that number will “anchor” the subsequent dealings. A striking illustration of anchoring is an experiment in which participants observed a roulette-style wheel that stopped on either 10 or 65, then were asked to guess what percentage of United Nations countries is African. The ones who saw the wheel stop on 10 guessed 25 percent, on average; the ones who saw the wheel stop on 65 guessed 45 percent. (The correct percentage at the time of the experiment was about 28 percent.)

The effects of biases do not play out just on an individual level. Last year, President Donald Trump decided to send more troops to Afghanistan, and thereby walked right into the sunk-cost fallacy. He said, “Our nation must seek an honorable and enduring outcome worthy of the tremendous sacrifices that have been made, especially the sacrifices of lives.” Sunk-cost thinking tells us to stick with a bad investment because of the money we have already lost on it; to finish an unappetizing restaurant meal because, after all, we’re paying for it; to prosecute an unwinnable war because of the investment of blood and treasure. In all cases, this way of thinking is rubbish.“We would all like to have a warning bell that rings loudly whenever we are about to make a serious error,” Kahneman writes, “but no such bell is available.”

If I had to single out a particular bias as the most pervasive and damaging, it would probably be confirmation bias. That’s the effect that leads us to look for evidence confirming what we already think or suspect, to view facts and ideas we encounter as further confirmation, and to discount or ignore any piece of evidence that seems to support an alternate view. Confirmation bias shows up most blatantly in our current political divide, where each side seems unable to allow that the other side is right about anything.

Confirmation bias plays out in lots of other circumstances, sometimes with terrible consequences. To quote the 2005 report to the president on the lead-up to the Iraq War: “When confronted with evidence that indicated Iraq did not have [weapons of mass destruction], analysts tended to discount such information. Rather than weighing the evidence independently, analysts accepted information that fit the prevailing theory and rejected information that contradicted it.”

The whole idea of cognitive biases and faulty heuristics—the shortcuts and rules of thumb by which we make judgments and predictions—was more or less invented in the 1970s by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, social scientists who started their careers in Israel and eventually moved to the United States. They were the researchers who conducted the African-countries-in-the-UN experiment. Tversky died in 1996. Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for the work the two men did together, which he summarized in his 2011 best seller, Thinking, Fast and Slow. Another best seller, last year’s The Undoing Project, by Michael Lewis, tells the story of the sometimes contentious collaboration between Tversky and Kahneman. Lewis’s earlier book Moneyball was really about how his hero, the baseball executive Billy Beane, countered the cognitive biases of old-school scouts—notably fundamental attribution error, whereby, when assessing someone’s behavior, we put too much weight on his or her personal attributes and too little on external factors, many of which can be measured with statistics.

Another key figure in the field is the University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler. One of the biases he’s most linked with is the endowment effect, which leads us to place an irrationally high value on our possessions. In an experiment conducted by Thaler, Kahneman, and Jack L. Knetsch, half the participants were given a mug and then asked how much they would sell it for. The average answer was $5.78. The rest of the group said they would spend, on average, $2.21 for the same mug. This flew in the face of classic economic theory, which says that at a given time and among a certain population, an item has a market value that does not depend on whether one owns it or not. Thaler won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics.

Most books and articles about cognitive bias contain a brief passage, typically toward the end, similar to this one in Thinking, Fast and Slow: “The question that is most often asked about cognitive illusions is whether they can be overcome. The message … is not encouraging.”

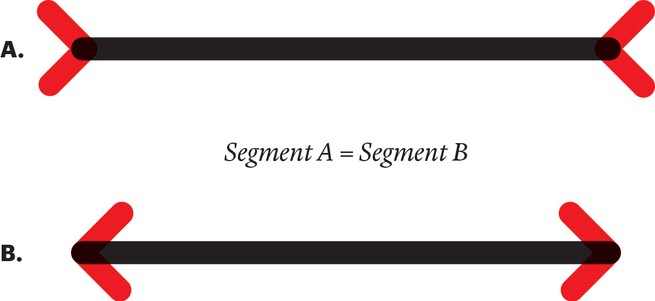

Kahneman and others draw an analogy based on an understanding of the Müller-Lyer illusion, two parallel lines with arrows at each end. One line’s arrows point in; the other line’s arrows point out. Because of the direction of the arrows, the latter line appears shorter than the former, but in fact the two lines are the same length. Here’s the key: Even after we have measured the lines and found them to be equal, and have had the neurological basis of the illusion explained to us, we still perceive one line to be shorter than the other.

At least with the optical illusion, our slow-thinking, analytic mind—what Kahneman calls System 2—will recognize a Müller-Lyer situation and convince itself not to trust the fast-twitch System 1’s perception. But that’s not so easy in the real world, when we’re dealing with people and situations rather than lines. “Unfortunately, this sensible procedure is least likely to be applied when it is needed most,” Kahneman writes. “We would all like to have a warning bell that rings loudly whenever we are about to make a serious error, but no such bell is available.”

Because biases appear to be so hardwired and inalterable, most of the attention paid to countering them hasn’t dealt with the problematic thoughts, judgments, or predictions themselves. Instead, it has been devoted to changing behavior, in the form of incentives or “nudges.” For example, while present bias has so far proved intractable, employers have been able to nudge employees into contributing to retirement plans by making saving the default option; you have to actively take steps in order to not participate. That is, laziness or inertia can be more powerful than bias. Procedures can also be organized in a way that dissuades or prevents people from acting on biased thoughts. A well-known example: the checklists for doctors and nurses put forward by Atul Gawande in his book The Checklist Manifesto.

Is it really impossible, however, to shed or significantly mitigate one’s biases? Some studies have tentatively answered that question in the affirmative. These experiments are based on the reactions and responses of randomly chosen subjects, many of them college undergraduates: people, that is, who care about the $20 they are being paid to participate, not about modifying or even learning about their behavior and thinking. But what if the person undergoing the de-biasing strategies was highly motivated and self-selected? In other words, what if it was me?

Naturally, I wrote to Daniel Kahneman, who at 84 still holds an appointment at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, at Princeton, but spends most of his time in Manhattan. He answered swiftly and agreed to meet. “I should,” he said, “at least try to talk you out of your project.”

I met with Kahneman at a Le Pain Quotidien in Lower Manhattan. He is tall, soft-spoken, and affable, with a pronounced accent and a wry smile. Over an apple pastry and tea with milk, he told me, “Temperament has a lot to do with my position. You won’t find anyone more pessimistic than I am.”

In this context, his pessimism relates, first, to the impossibility of effecting any changes to System 1—the quick-thinking part of our brain and the one that makes mistaken judgments tantamount to the Müller-Lyer line illusion. “I see the picture as unequal lines,” he said. “The goal is not to trust what I think I see. To understand that I shouldn’t believe my lying eyes.” That’s doable with the optical illusion, he said, but extremely difficult with real-world cognitive biases.

The most effective check against them, as Kahneman says, is from the outside: Others can perceive our errors more readily than we can. And “slow-thinking organizations,” as he puts it, can institute policies that include the monitoring of individual decisions and predictions. They can also require procedures such as checklists and “premortems,” an idea and term thought up by Gary Klein, a cognitive psychologist. A premortem attempts to counter optimism bias by requiring team members to imagine that a project has gone very, very badly and write a sentence or two describing how that happened. Conducting this exercise, it turns out, helps people think ahead.

“My position is that none of these things have any effect on System 1,” Kahneman said. “You can’t improve intuition. Perhaps, with very long-term training, lots of talk, and exposure to behavioral economics, what you can do is cue reasoning, so you can engage System 2 to follow rules. Unfortunately, the world doesn’t provide cues. And for most people, in the heat of argument the rules go out the window.

“That’s my story. I really hope I don’t have to stick to it.”

As it happened, right around the same time I was communicating and meeting with Kahneman, he was exchanging emails with Richard E. Nisbett, a social psychologist at the University of Michigan. The two men had been professionally connected for decades. Nisbett was instrumental in disseminating Kahneman and Tversky’s work, in a 1980 book called Human Inference: Strategies and Shortcomings of Social Judgment. And in Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman describes an even earlier Nisbett article that showed subjects’ disinclination to believe statistical and other general evidence, basing their judgments instead on individual examples and vivid anecdotes. (This bias is known as base-rate neglect.)

But over the years, Nisbett had come to emphasize in his research and thinking the possibility of training people to overcome or avoid a number of pitfalls, including base-rate neglect, fundamental attribution error, and the sunk-cost fallacy. He had emailed Kahneman in part because he had been working on a memoir, and wanted to discuss a conversation he’d had with Kahneman and Tversky at a long-ago conference. Nisbett had the distinct impression that Kahneman and Tversky had been angry—that they’d thought what he had been saying and doing was an implicit criticism of them. Kahneman recalled the interaction, emailing back: “Yes, I remember we were (somewhat) annoyed by your work on the ease of training statistical intuitions (angry is much too strong).”

When Nisbett has to give an example of his approach, he usually brings up the baseball-phenom survey. This involved telephoning University of Michigan students on the pretense of conducting a poll about sports, and asking them why there are always several Major League batters with .450 batting averages early in a season, yet no player has ever finished a season with an average that high. When he talks with students who haven’t taken Introduction to Statistics, roughly half give erroneous reasons such as “the pitchers get used to the batters,” “the batters get tired as the season wears on,” and so on. And about half give the right answer: the law of large numbers, which holds that outlier results are much more frequent when the sample size (at bats, in this case) is small. Over the course of the season, as the number of at bats increases, regression to the mean is inevitable. When Nisbett asks the same question of students who have completed the statistics course, about 70 percent give the right answer. He believes this result shows, pace Kahneman, that the law of large numbers can be absorbed into System 2—and maybe into System 1 as well, even when there are minimal cues.

Nisbett’s second-favorite example is that economists, who have absorbed the lessons of the sunk-cost fallacy, routinely walk out of bad movies and leave bad restaurant meals uneaten.

I spoke with Nisbett by phone and asked him about his disagreement with Kahneman. He still sounded a bit uncertain. “Danny seemed to be convinced that what I was showing was trivial,” he said. “To him it was clear: Training was hopeless for all kinds of judgments. But we’ve tested Michigan students over four years, and they show a huge increase in ability to solve problems. Graduate students in psychology also show a huge gain.”

Nisbett writes in his 2015 book, Mindware: Tools for Smart Thinking, “I know from my own research on teaching people how to reason statistically that just a few examples in two or three domains are sufficient to improve people’s reasoning for an indefinitely large number of events.”

In one of his emails to Nisbett, Kahneman had suggested that the difference between them was to a significant extent a result of temperament: pessimist versus optimist. In a response, Nisbett suggested another factor: “You and Amos specialized in hard problems for which you were drawn to the wrong answer. I began to study easy problems, which you guys would never get wrong but untutored people routinely do … Then you can look at the effects of instruction on such easy problems, which turn out to be huge.”

An example of an easy problem is the .450 hitter early in a baseball season. An example of a hard one is “the Linda problem,” which was the basis of one of Kahneman and Tversky’s early articles. Simplified, the experiment presented subjects with the characteristics of a fictional woman, “Linda,” including her commitment to social justice, college major in philosophy, participation in antinuclear demonstrations, and so on. Then the subjects were asked which was more likely: (a) that Linda was a bank teller, or (b) that she was a bank teller and active in the feminist movement. The correct answer is (a), because it is always more likely that one condition will be satisfied in a situation than that the condition plus a second one will be satisfied. But because of the conjunction fallacy (the assumption that multiple specific conditions are more probable than a single general one) and the representativeness heuristic (our strong desire to apply stereotypes), more than 80 percent of undergraduates surveyed answered (b).

Nisbett justifiably asks how often in real life we need to make a judgment like the one called for in the Linda problem. I cannot think of any applicable scenarios in my life. It is a bit of a logical parlor trick.

Nisbett suggested that I take “Mindware: Critical Thinking for the Information Age,” an online Coursera course in which he goes over what he considers the most effective de-biasing skills and concepts. Then, to see how much I had learned, I would take a survey he gives to Michigan undergraduates. So I did.

The course consists of eight lessons by Nisbett—who comes across on-screen as the authoritative but approachable psych professor we all would like to have had—interspersed with some graphics and quizzes. I recommend it. He explains the availability heuristic this way: “People are surprised that suicides outnumber homicides, and drownings outnumber deaths by fire. People always think crime is increasing” even if it’s not.

He addresses the logical fallacy of confirmation bias, explaining that people’s tendency, when testing a hypothesis they’re inclined to believe, is to seek examples confirming it. But Nisbett points out that no matter how many such examples we gather, we can never prove the proposition. The right thing to do is to look for cases that would disprove it.

And he approaches base-rate neglect by means of his own strategy for choosing which movies to see. His decision is never dependent on ads, or a particular review, or whether a film sounds like something he would enjoy. Instead, he says, “I live by base rates. I don’t read a book or see a movie unless it’s highly recommended by people I trust.

“Most people think they’re not like other people. But they are.”

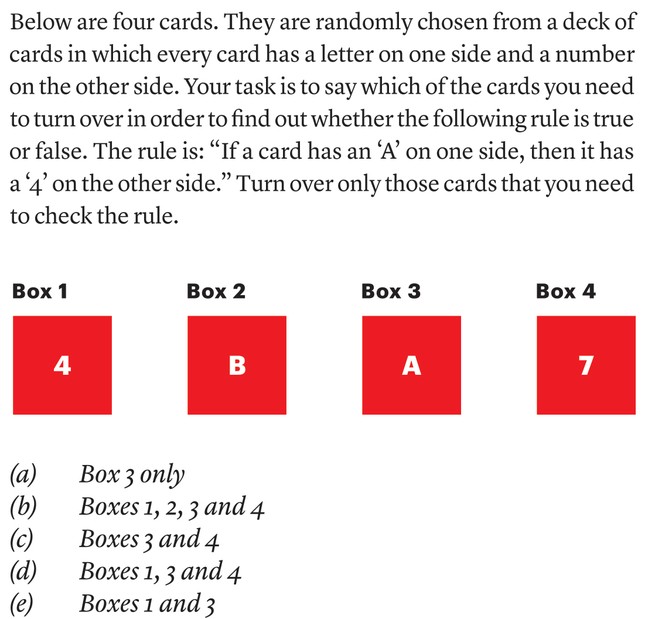

When I finished the course, Nisbett sent me the survey he and colleagues administer to Michigan undergrads. It contains a few dozen problems meant to measure the subjects’ resistance to cognitive biases. For example:

Because of confirmation bias, many people who haven’t been trained answer (e). But the correct answer is (c). The only thing you can hope to do in this situation is disprove the rule, and the only way to do that is to turn over the cards displaying the letter A (the rule is disproved if a number other than 4 is on the other side) and the number 7 (the rule is disproved if an A is on the other side).

I got it right. Indeed, when I emailed my completed test, Nisbett replied, “My guess is that very few if any UM seniors did as well as you. I’m sure at least some psych students, at least after 2 years in school, did as well. But note that you came fairly close to a perfect score.”

Nevertheless, I did not feel that reading Mindware and taking the Coursera course had necessarily rid me of my biases. For one thing, I hadn’t been tested beforehand, so I might just be a comparatively unbiased guy. For another, many of the test questions, including the one above, seemed somewhat remote from scenarios one might encounter in day-to-day life. They seemed to be “hard” problems, not unlike the one about Linda the bank teller. Further, I had been, as Kahneman would say, “cued.” In contrast to the Michigan seniors, I knew exactly why I was being asked these questions, and approached them accordingly.

For his part, Nisbett insisted that the results were meaningful. “If you’re doing better in a testing context,” he told me, “you’ll jolly well be doing better in the real world.”

Nisbett’s coursera course and Hal Hershfield’s close encounters with one’s older self are hardly the only de-biasing methods out there. The New York–based NeuroLeadership Institute offers organizations and individuals a variety of training sessions, webinars, and conferences that promise, among other things, to use brain science to teach participants to counter bias. This year’s two-day summit will be held in New York next month; for $2,845, you could learn, for example, “why are our brains so bad at thinking about the future, and how do we do it better?”

Philip E. Tetlock, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, and his wife and research partner, Barbara Mellers, have for years been studying what they call “superforecasters”: people who manage to sidestep cognitive biases and predict future events with far more accuracy than the pundits and so-called experts who show up on TV. In Tetlock’s book Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (co-written with Dan Gardner), and in the commercial venture he and Mellers co-founded, Good Judgment, they share the superforecasters’ secret sauce.

One of the most important ingredients is what Tetlock calls “the outside view.” The inside view is a product of fundamental attribution error, base-rate neglect, and other biases that are constantly cajoling us into resting our judgments and predictions on good or vivid stories instead of on data and statistics. Tetlock explains, “At a wedding, someone sidles up to you and says, ‘How long do you give them?’ If you’re shocked because you’ve seen the devotion they show each other, you’ve been sucked into the inside view.” Something like 40 percent of marriages end in divorce, and that statistic is far more predictive of the fate of any particular marriage than a mutually adoring gaze. Not that you want to share that insight at the reception.

The recent de-biasing interventions that scholars in the field have deemed the most promising are a handful of video games. Their genesis was in the Iraq War and the catastrophic weapons-of-mass-destruction blunder that led to it, which left the intelligence community reeling. In 2006, seeking to prevent another mistake of that magnitude, the U.S. government created the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (iarpa), an agency designed to use cutting-edge research and technology to improve intelligence-gathering and analysis. In 2011, iarpa initiated a program, Sirius, to fund the development of “serious” video games that could combat or mitigate what were deemed to be the six most damaging biases: confirmation bias, fundamental attribution error, the bias blind spot (the feeling that one is less biased than the average person), the anchoring effect, the representativeness heuristic, and projection bias (the assumption that everybody else’s thinking is the same as one’s own).Confirmation bias—probably the most pervasive and damaging bias of them all—leads us to look for evidence that confirms what we already think.

Six teams set out to develop such games, and two of them completed the process. The team that has gotten the most attention was led by Carey K. Morewedge, now a professor at Boston University. Together with collaborators who included staff from Creative Technologies, a company specializing in games and other simulations, and Leidos, a defense, intelligence, and health research company that does a lot of government work, Morewedge devised Missing. Some subjects played the game, which takes about three hours to complete, while others watched a video about cognitive bias. All were tested on bias-mitigation skills before the training, immediately afterward, and then finally after eight to 12 weeks had passed.

After taking the test, I played the game, which has the production value of a late-2000s PlayStation 3 first-person offering, with large-chested women and men, all of whom wear form-fitting clothes and navigate the landscape a bit tentatively. The player adopts the persona of a neighbor of a woman named Terry Hughes, who, in the first part of the game, has mysteriously gone missing. In the second, she has reemerged and needs your help to look into some skulduggery at her company. Along the way, you’re asked to make judgments and predictions—some having to do with the story and some about unrelated issues—which are designed to call your biases into play. You’re given immediate feedback on your answers.

For example, as you’re searching Terry’s apartment, the building superintendent knocks on the door and asks you, apropos of nothing, about Mary, another tenant, whom he describes as “not a jock.” He says 70 percent of the tenants go to Rocky’s Gym, 10 percent go to Entropy Fitness, and 20 percent just stay at home and watch Netflix. Which gym, he asks, do you think Mary probably goes to? A wrong answer, reached thanks to base-rate neglect (a form of the representativeness heuristic) is “None. Mary is a couch potato.” The right answer—based on the data the super has helpfully provided—is Rocky’s Gym. When the participants in the study were tested immediately after playing the game or watching the video and then a couple of months later, everybody improved, but the game players improved more than the video watchers.

When I spoke with Morewedge, he said he saw the results as supporting the research and insights of Richard Nisbett. “Nisbett’s work was largely written off by the field, the assumption being that training can’t reduce bias,” he told me. “The literature on training suggests books and classes are fine entertainment but largely ineffectual. But the game has very large effects. It surprised everyone.”

I took the test again soon after playing the game, with mixed results. I showed notable improvement in confirmation bias, fundamental attribution error, and the representativeness heuristic, and improved slightly in bias blind spot and anchoring bias. My lowest initial score—44.8 percent—was in projection bias. It actually dropped a bit after I played the game. (I really need to stop assuming that everybody thinks like me.) But even the positive results reminded me of something Daniel Kahneman had told me. “Pencil-and-paper doesn’t convince me,” he said. “A test can be given even a couple of years later. But the test cues the test-taker. It reminds him what it’s all about.”

I had taken Nisbett’s and Morewedge’s tests on a computer screen, not on paper, but the point remains. It’s one thing for the effects of training to show up in the form of improved results on a test—when you’re on your guard, maybe even looking for tricks—and quite another for the effects to show up in the form of real-life behavior. Morewedge told me that some tentative real-world scenarios along the lines of Missing have shown “promising results,” but that it’s too soon to talk about them.

Iam neither as much of a pessimist as Daniel Kahneman nor as much of an optimist as Richard Nisbett. Since immersing myself in the field, I have noticed a few changes in my behavior. For example, one hot day recently, I decided to buy a bottle of water in a vending machine for $2. The bottle didn’t come out; upon inspection, I realized that the mechanism holding the bottle in place was broken. However, right next to it was another row of water bottles, and clearly the mechanism in that row was in order. My instinct was to not buy a bottle from the “good” row, because $4 for a bottle of water is too much. But all of my training in cognitive biases told me that was faulty thinking. I would be spending $2 for the water—a price I was willing to pay, as had already been established. So I put the money in and got the water, which I happily drank.

In the future, I will monitor my thoughts and reactions as best I can. Let’s say I’m looking to hire a research assistant. Candidate A has sterling references and experience but appears tongue-tied and can’t look me in the eye; Candidate B loves to talk NBA basketball—my favorite topic!—but his recommendations are mediocre at best. Will I have what it takes to overcome fundamental attribution error and hire Candidate A?

Or let’s say there is an officeholder I despise for reasons of temperament, behavior, and ideology. And let’s further say that under this person’s administration, the national economy is performing well. Will I be able to dislodge my powerful confirmation bias and allow the possibility that the person deserves some credit?

As for the matter that Hal Hershfield brought up in the first place—estate planning—I have always been the proverbial ant, storing up my food for winter while the grasshoppers sing and play. In other words, I have always maxed out contributions to 401(k)s, Roth IRAs, Simplified Employee Pensions, 403(b)s, 457(b)s, and pretty much every alphabet-soup savings choice presented to me. But as good a saver as I am, I am that bad a procrastinator. Months ago, my financial adviser offered to evaluate, for free, my will, which was put together a couple of decades ago and surely needs revising. There’s something about drawing up a will that creates a perfect storm of biases, from the ambiguity effect (“the tendency to avoid options for which missing information makes the probability seem ‘unknown,’ ” as Wikipedia defines it) to normalcy bias (“the refusal to plan for, or react to, a disaster which has never happened before”), all of them culminating in the ostrich effect (do I really need to explain?). My adviser sent me a prepaid FedEx envelope, which has been lying on the floor of my office gathering dust. It is still there. As hindsight bias tells me, I knew that would happen.