BY TUNIKA ONNEKIKAMI DECEMBER 6, 2021 Atlas Obscura

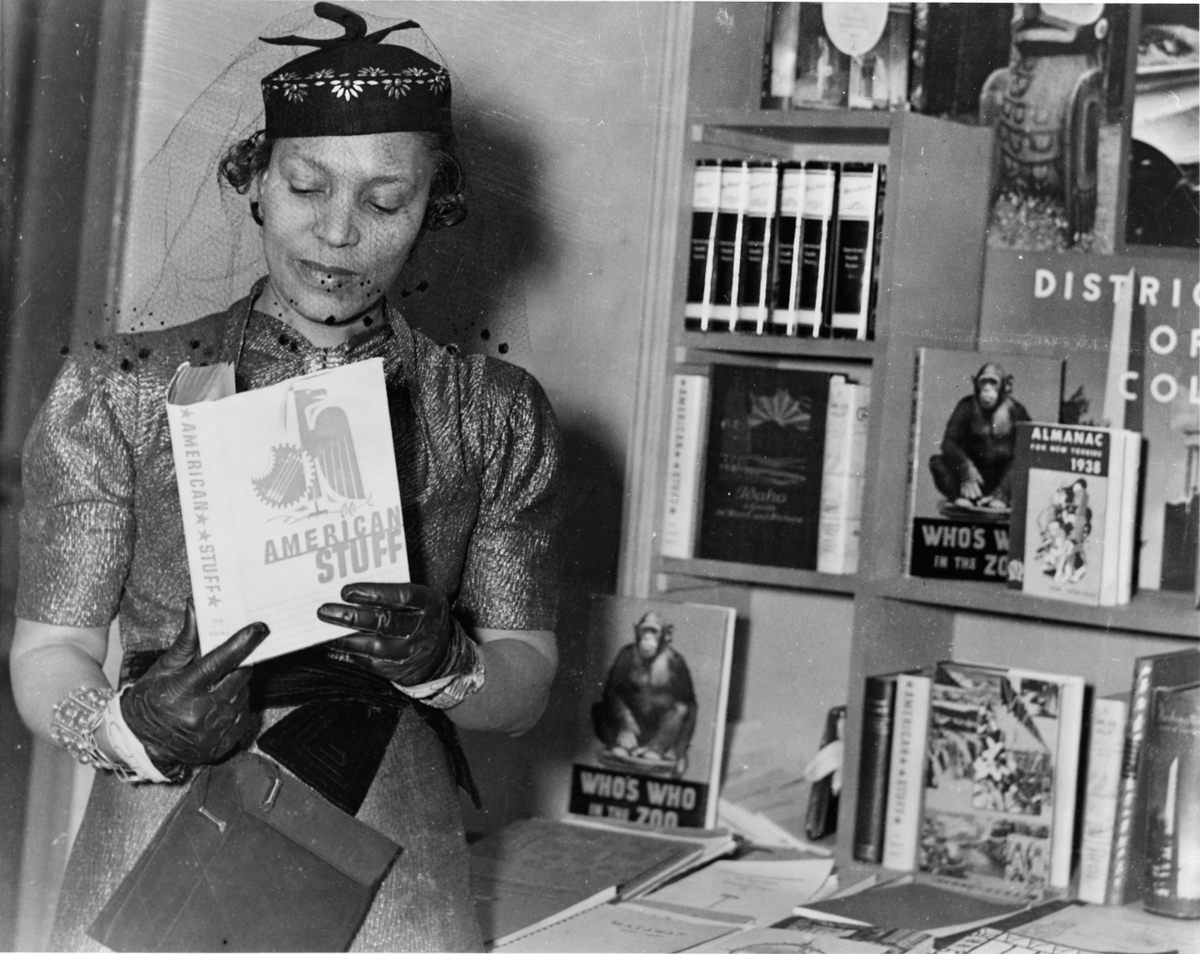

AS FAR AS MARJORIE HARRELL knew, her sophomore English teacher in 1958 was just an old woman—quiet, tired, a bit sick. It was only after the teacher died a couple of years later that Harrell learned that she had been one of the most unique, critical figures in Black literature and culture during the 20th century. Harrell, a historian who grew up and still lives in Fort Pierce, Florida, a small coastal city halfway between Miami and Daytona Beach, realized years later that her teacher was Zora Neale Hurston, the world-renowned author of Their Eyes Were Watching God—a 1937 novel considered a classic of both the Harlem Renaissance and the American South.

For Harrell, the belated realization—some three decades later—was a spark. In 2004, with support from the larger Fort Pierce community, Harrell and others established the Zora Neale Hurston Dust Tracks Heritage Trail, named for Hurston’s 1942 autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road. It offers “all of the places she touched when she was alive,” Harrell says.

The trail, on its own, isn’t much. It highlights eight locations, with informational markers, that were relevant to Hurston’s life and final years in Fort Pierce. But the history it encodes into the city, of Black life thriving on its own during segregation in the American South, is monumental.

“Zora Neale Hurston was the best writer of Black literature there was,” Harrell says. “She was better than James Baldwin, because she used the language and she didn’t change anything. Zora told it like we talked and like we were.”

Hurston had spent her final years in lush and colorful Fort Pierce, along the Treasure Coast, some 30 years after her time as a core figure of the Harlem Renaissance and a subsequent career traveling and writing as an anthropologist.

In 1957, newspaper publisher C.E. Bolen convinced Hurston to move to Fort Pierce and write for his local Black newspaper, The Chronicle. He made promises he couldn’t keep. “He would tell you he was going to give you this big check, and the big checks never came,” Harrell says with a laugh, but Bolen connected Hurston with Clem C. Benton, a local physician and community leader.

Benton helped her get a position teaching English at a Lincoln Park Academy (trail marker 2), and offered her a small home he owned (trail marker 3), where she could live rent-free. Both were a short walk from the building that housed The Chronicle (trail marker 5). This triangle formed the core of Hurston’s life in Fort Pierce. But there was more to it than that.

Outside of writing and teaching, Hurston kept a fairly active social calendar—one that often intrigued and shocked Fort Pierce’s Black community. She spent time with Benton and his family, joining them on Sundays for meals prepared by his daughter Arlena and Margaret, and acquainted herself with other Black people around town. But she also befriended white people—uncommon in the Jim Crow South. Hurston frequented the home of A.E. Backus (trail marker 8), a white artist who supported Black artists and writers. Harrell says that Hurston was the only Black person around who could walk through the front doors of the white people who lived downtown.

Throughout her life, Hurston paid little mind to the limitations that were supposed to come with her race or gender. She grew up in Eatonville, Florida, one of the first all-Black towns to be incorporated in Florida (in 1887) and only 130 miles from Fort Pierce. To her, the self-sufficiency of Black communities was the norm, despite and to some extent because of segregation.

Later, Hurston studied at Barnard College in New York under pioneering anthropologist Franz Boas, whose ideas on cultural relativism heavily influenced her own research and thinking as an anthropologist and folklorist. During her studies and after, she traveled throughout the South and the Caribbean, studying Black cultures and rituals—both the basis of her fieldwork and the inspiration for her fiction.

Hurston carried this self-assuredness into her life in Fort Pierce, even as life began to take its toll.

Hurston lived in her Fort Pierce home, through financial struggles, until she suffered a stroke in late 1959. She lived out her final days in a welfare home for Black people, and died on January 28, 1960. Her friends and acquaintances around Fort Pierce and beyond raised funds for her funeral, held at Peek’s Funeral Home, now Sarah’s Memorial Chapel (trail marker 7).

Hurston was buried in a donated plot in the Garden of Heavenly Rest (trail marker 4). By the time Harrell and others were choosing spots for the historical trail, Hurston’s time in Fort Pierce had already been memorialized in a few ways. Renowned Black writer Alice Walker’s impactful 1975 essay “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” in Ms. Magazine described Walker’s experience in Fort Pierce, which included her placing a tombstone on Hurston’s grave: “A GENIUS OF THE SOUTH.”

Walker’s essay helped what is now officially the Zora Neale Hurston House, an unassuming, flat-roofed box, gain National Historic Landmark designation in 1991. Page Putnam Miller, a former lobbyist for the National Coordinating Committee for the Promotion of History, nominated Hurston’s final home for protection. Miller’s team had been charged with helping the National Park Service add more landmarks to celebrate great American women, and in nominating Hurston’s home was tasked with educating the voting committee about her.

“[Getting Zora’s House designated] was a particular challenge,” Miller says. “We had to educate the committee and overcome the architectural bias that was built into the ways National Historic Landmarks had been approached in the past.”

While maintaining this heritage has been challenging, “the local community is very supportive of the trail and Zora,” says Kathleen Flynn, a librarian at the posthumously dedicated Zora Neale Hurston Branch Library in Fort Pierce (trail marker 1). Community members, she says, are largely responsible for keeping the sites intact. For example, the old Chronicle building is now owned by Tessa Jeanne Adams, Harrell’s daughter—and Harrell herself now lives there as well.

Marvin Hobson, current president of the Zora Neale Hurston Florida Education Foundation and an associate professor at Indian River State College, worked with Harrell and members of the nonprofit organization to acquire, in 2019, the building in which Hurston died, now the Agape Senior Recreation Center. The center already features a Hurston exhibit, and recently gained a local historic designation from St. Lucie County. The Foundation is working to raise $600,000 for renovations, which will include changing its name and turning it into a museum and community center in Hurston’s honor.

Limited awareness, resources, and funding means that the work to maintain Hurston’s legacy continues—work that falls largely to volunteers dedicated to preserving the writer’s contributions to Black culture and literature.

“[Hurston] wasn’t worrying about who was going to take care of her, or her finances even. She was able to see the work that she had right in front of her and focus on that and allowed other people to take care of her, and that worked for her,” Hobson says. “She was provided for by doing her work and that’s what we’re trying to do.”