:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/adn/MTVGDOYYBVDFNNLXFNHKZYFYNY.jpg)

By Paulina Firozi, The Washington Post December 19th 2021

Nathan Asher was scrolling through pages and pages of therapists. Starting in January, just shy of a year into the pandemic, they were looking for someone who could help with what felt like a crescendo of anxiety.

Asher, now 18 and a freshman at Appalachian State University in Boone, N.C., said around that time, things kept piling up. Facing mounting stress and burnout, Asher quit the French horn after six years only to pick up an entirely new instrument as they were applying to colleges for music. Their mother had recently been diagnosed with breast cancer, so their family was “pretty hard-core in lockdown because we didn’t want to put her at risk at all,” Asher said. Under the weight of it all, Asher was struggling and wanted help.

Multiple boxes needed to be checked: The therapist needed to offer virtual sessions or be nearby their North Carolina home. The therapist would need to be gender-affirming and familiar with LGBT patients, and would need to provide what felt like a supportive space.

But every search, Asher would come up short.

“I didn’t need an addiction therapist, I didn’t need a faith therapist, I didn’t need a relationship therapist,” they said. “I was calling and sending emails and very rarely would I get a reply back.”

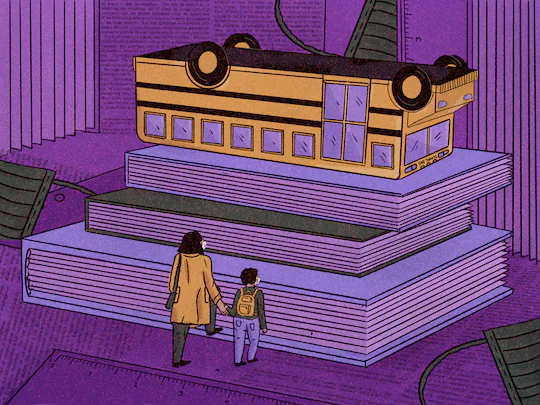

Asher’s search for care came as health professionals say mental health challenges among youth and their families have skyrocketed, exacerbated in the last couple of years in part because of the pandemic. Over the past year and a half, they say the stressors that young people experience even normally have been amplified, disproportionately impacting communities hit hardest by the pandemic. For some, this has meant scrambling for care as demand swells and as some are left behind because of lack of access. Still, as public awareness grows around mental well-being, others are creating new outlets for relief when things get to be too much.

The message has only grown louder in recent months. In late October, three prominent medical groups declared a national state of emergency in children’s mental health. A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that while suicide rates dropped in 2020 overall, that wasn’t the case for younger Americans, with a slight uptick in suicides among all age groups 10 to 34, and a significant 5 percent increase among 25-to-34-year-olds. On Dec. 7, the nation’s top physician released a 53-page report that serves as an exclamation point on the warning that young people are in a crisis, saying the cumulative effect of the challenges they grapple with has been “devastating.”

“On the ground, in our clinics and hospitals, we’ve been seeing really increasing numbers of children with mental health concerns,” said Lee Savio Beers, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “A lot of what we’re seeing is more severe, and it’s getting harder and harder to access care. It just really felt like it was at a tipping point where we’re just seeing so many kids who are in need of support and without enough resources.”

[Suicide attempts among younger Alaskans have risen even as overall suicide deaths declined in 2020]

Beers, whose group was one of the three that made the declaration, detailed the ways education and normal activities for young people have been disrupted. Many have faced significant amounts of loss and grief. And these impacts on youth are disparate – the pandemic has had a profoundly disproportionate impact on communities of color.

“With the pandemic being such that it’s so isolating with us quarantining and socially distancing, I think people’s rates of depression, anxiety, for those who experienced trauma, maybe even PTSD, have gone up,” said Ernestine Briggs-King, a psychologist and Duke University associate professor. “And yet it’s been harder to access services – even though in some ways it’s been easier.”

Briggs-King said a ramp up in virtual therapy offerings during the pandemic in some ways increased whom providers have been able to reach, and allowed some people more options for accessing care. But she said people without equal access to telemedicine, perhaps because of a lack of Internet or smartphone access, have been left behind.

For some young people, increased demand for online therapy meant providers were booked and unavailable in times of need.

This year was not Asher’s first time searching for mental health care – they had previously struggled with depression in ninth grade. Around that time, they said they realized they were transgender. Asher came out that summer at a music camp, and then switched schools entirely going into 10th grade.

Asher had previously been diagnosed with a “mild episode of a major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder,” they said. So when stress during the pandemic accumulated, Asher knew how to look for a therapist. But this time, there were new obstacles, compounded by the public health crisis.

It took three months before Asher was able to find a therapist “because all of the telehealth therapists were full, and a lot of normal therapists were not wanting to make the switch to teletherapy.”

When they finally found someone to connect with, the therapist suggested Asher get an evaluation for ADHD. That evaluation wouldn’t happen until June.

“So I spent a good six months just kind of ruminating about the fact that I may or may not have ADHD,” Asher said. After that appointment, Asher said, they were diagnosed with autism, in addition to a confirmed ADHD diagnosis. The right diagnosis came as both a relief and its own source of stress – they began to understand underlying causes of their experiences, but it meant Asher needed to find more help, more answers, and perhaps face more roadblocks, as the pandemic continued.

“You start to realize, ‘Wow, this system is not made to support me,’ ” Asher said. “This system is not made to be accessible.”

Even before the pandemic, “we were in the middle of a children’s mental health crisis,” said Nathaniel Counts, a senior vice president of behavioral health innovation for Mental Health America.

He said in the decade before the pandemic, rates of adolescent major depressive episodes surged, and rates of children presenting in the emergency department for self-harm and suicidal ideation were increasing.

Then the pandemic hit, bringing its own set of burdens.

“The two words I’d used to describe it are disruption and stress,” he said. “The way that covid affected children is very different, depending on the child. But the common theme is it disrupted your day-to-day activities and created a new set of stressors for your family and for yourself.”

In big ways and small, the enduring public health crisis may have dramatically changed the daily world of a child or teen.

There were missed days of school, canceled sports competitions, skipped playdates; loss of access to mental health care or social services or food; loss of loved ones – the U.S. Surgeon General’s report cites these and a multitude of other unprecedented challenges that could have played a role in overall mental well-being.

Since the pandemic’s start, the report says “rates of psychological distress among young people, including symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders, have increased.” It points to recent research covering 80,000 young people worldwide that found depressive and anxiety symptoms doubled during this time.

There is also a growing public awareness about youth mental health that is partly a result of young people themselves discussing the issue and reducing the stigma, including through social media, said Danielle Ramo, a clinical psychologist and chief clinical officer at BeMe Health, a digital mental health platform for teens.

“Some of it is just broadly this generation being a bit more open in talking about their struggles,” she said. “And the plethora of the social world and the internet makes those conversations more public.”

Sreeya Pittala found herself struggling a few months into the pandemic and virtual school. Feeling “more alone than ever,” she said she wanted a place to have an open conversation about mental health, something she felt her school was missing.

So Pittala, now an 18-year-old senior at Newark Charter School in Delaware, started a chapter of Bring Change to Mind, a national nonprofit with student-led clubs at high schools across the country.

The group started meeting virtually, an outlet for members to talk about any struggles or anxiety related to school. At the time, there was plenty fueling that stress.

Going through the motions of high school behind a screen became an unending task, Pittala said. There were always assignments to complete even while the options for a respite – a lunch break at school with peers, time with friends at all – had been taken away. Even when calls with friends were scheduled, Pittala said, they were often for the purpose of working together on school assignments rather than “scheduling a call just to talk about life.”

She described the pandemic for teenagers as “pretty lonely.”

“It was just really unmotivating and exhausting. It felt miserable at times,” she said.

In its October declaration, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Children’s Hospital Association called for increased federal funding for mental health screenings, diagnosis and treatment. It also urged increased funding for and implementation of mental health care in schools.

“If you have really strong mental health and social emotional programing in schools that’s focusing on health promotion, that’s going to help create an environment that is more supportive of all children,” Beers said.

In November, the chief executive of the Children’s Hospital Association submitted a letter to the Senate Finance Committee calling for support for children’s mental health. The group said the letter was in response to an earlier request from lawmakers for input on ways to “develop bipartisan legislation to address barriers to mental health care” amid worsening trends during the pandemic.

In his recent advisory, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy said it would take an “all-of-society” effort to address mental health, and urged action.

“It would be a tragedy if we beat back one public health crisis only to allow another to grow in its place,” Murthy said.

Jessica Caballero, 17, is also involved in a Bring Change to Mind club at West Ranch High School in Stevenson Ranch, Calif. Even before the pandemic, she described a challenging start to the school year that began in 2019. There were fires near where she lives in Southern California. In the fall, she went into lockdown when there was a shooting at another school in the district.

“It wasn’t really a good year for any of us, you could say – all this stress and anxiety,” she said. “When covid hit, it just hit all of us pretty hard.”

She remembers thinking she’d have just a couple of weeks off school. Then her aquatic club team practices were canceled. The in-person school year vanished.

“It really left me in a state of isolation,” she said.

She found solace in her family and her little siblings. She also found comfort in the club meetings that provided a place to talk openly about mental health.

“As a Mexican American Peruvian, mental health was never a huge topic in my household. It was always kind of seen as a choice like, ‘Oh, are you depressed? Just be happy. You have no reason to feel like this,’ ” Caballero said. “So I never really had this kind of strong connection with anybody in particular, especially when it came to talking about my own struggles.”

She said she wishes “more people just validated the feelings of people who need to talk and who need help.”

Counts said he believes young people should also be “directly engaged” with coming up with solutions for meeting youth mental health needs.

“The world of children is changing so rapidly, far more rapidly than I think adults can grapple with,” he said. “Only young people really have that kind of fundamental insight into what it is they need.”

Beyond school walls, Briggs-King said, it helps to have resources and sources of support in any space young people are in. That can come from coaches, teachers or neighbors – because when an entire community understands more about trauma, it may be better equipped to notice when issues arise.

She said: “Then you have a piece to communicate about a topic of conversation: ‘You know, I was worried about you. How are you sleeping? I know you’re not hanging out with your friends, you’re not playing sports – are you OK? Is there anything going on?’ “

Having an understanding of mental health and trauma can also help people communicate what they are feeling, she said, and can help families and friends pay attention to signs and express concerns they may have about loved ones.

Briggs-King added: “My mama used to say, ‘You know better, you do better.’

If you or someone you know needs help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255). You can also text a crisis counselor by messaging the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

The Washington Post’s Dave Jorgenson and Chris Vazquez contributed to this