By David S. Rotenstein from the Metropole

THE OFFICIAL BLOG OF THE URBAN HISTORY ASSOCIATION

In 2009 I learned about one African American woman who briefly lived in Silver Spring, Maryland, a Washington, DC, suburb. She worked for a white physician’s family. Lucille Walker’s story as a Black domestic worker survives in bits and pieces in the memory of the physician’s daughter, Ann Scandiffio. In 1939 Scandiffio’s parents bought a home in the Northwood Park subdivision. Laid out three years earlier, Northwood Park’s 198 original homesites had racially restrictive deed covenants. Mario Scandiffio was a pediatrician and Pauline Scandiffio had been a nightclub singer and federal employee. Their first child, Frank, was born in 1943, and Ann was born in 1944.

When I interviewed Ann Scandiffio in 2009, she recalled very little about Walker: her first name, the name that she and her brother called Walker (“Sha”), and some of the things that Walker did for her. Until 2022, when the National Archives and Records Administration released the 1950 census, Lucille Walker’s story was a dead end. With the new census information, I learned her last name and a few more biographical details—that she was 40 years old in 1940 and a divorced Tennessee native.[1]

The new information wasn’t much, but it was enough to tease additional details from Ann Scandiffio. Now 78, Scandiffio recalled Walker’s trips with the family to a vacation home and a few details about Walker’s personal life. She also recalled the tense last meeting her family had with Walker in a Washington hotel shortly after the Scandiffios had moved to Florida.

Over the next decade, my research on suburban gentrification and erasure exposed me to more stories about the Black women who cleaned homes and who helped to raise generations of middle- and upper-class white children. In my oral histories with whites who had moved into suburbia and the African Americans who lived in rural hamlets on suburban margins, I began looking for the stories of these women. Historians of Black suburbanization and Black communities affected by white suburbanization have noted the parallel work worlds of men and women in these spaces.[2] The women’s stories are not easy to find, but they exist.

Many twentieth-century American residential subdivisions were segregated. Most of those were neighborhoods where racially restrictive deed covenants enforced ethnic and racial homogeneity. Others were conceived by Blacks to create communities free from white surveillance and violence.[3] The covenant-restricted subdivisions were mini-sundown towns—white spaces where Blacks could not live unless they were employed by white homeowners. The Black women and men who worked and who slept in these homes are mostly invisible in the histories of suburbia. This post explores the research potential of looking for Black history in white spaces.

White Spaces and Black Spaces

The Black space and the white space are very different products of segregation that have outlived Jim Crow. “White spaces vary in kind, but their most visible and distinctive feature is their overwhelming presence of white people and their absence of black people,” wrote sociologist Elijah Anderson.[4] Residential subdivisions became white spaces through the creation of a white spatial imaginary—spaces defined by exclusion where the exchange value of housing becomes a dominant principle.[5] Whites go to great lengths to protect their investments in identity and wealth, erecting real and symbolic barriers to exclude Blacks and others considered non-white by virtue of race and religion. Place attachment and the blurred divisions demarcating domesticity and work spaces (use values) are subordinated in suburban America, where the value of land supersedes all else.[6]

Few instruments have better reinforced white spaces than racially restrictive deed covenants. Deed covenants comprised an essential link in an exclusionary chain blocking Blacks from white spaces. They were the cornerstone of sundown suburbs, sundown towns’ carefully planned kin.[7] Until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that they were unenforceable in 1948, racially restrictive deed covenants enforced housing segregation beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century.[8] Housing segregation, in turn, contributed to an array of inequities, from uneven access to education and employment to the loss of intergenerational wealth.[9] The segregated subdivision was segregated housing’s cornerstone and the ultimate white space.

Black spaces emerged in resistance to white spaces. They are not the residential neighborhoods kept white by racially restrictive deed covenants. They are not the parks and recreational spaces where Blacks were excluded. They are not businesses that didn’t take Black money or forced Black people to go to balconies, side windows, and back doors. Black spaces are those that are bound by mutual cooperation where the residents converted segregation into congregation. Though they were established on the margins of white society and were frequently stigmatized, these spaces and places became resilient and proud communities.[10]

Black Meccas like Atlanta and Harlem are well-known Black spaces. The thousands of Black towns, like the Freedom Colonies in Texas or such cities as Eatonville, Florida, and Mound Bayou, Mississippi, are also Black spaces. And then there are the Black suburbs—former Reconstruction-era hamlets and neighborhoods and intentionally planned communities—that are also Black spaces.[11] Collectively, these places comprise a “Black Map” of North America that is a guide to how historians may be able to surface stories of the Black experience inside such white spaces as sundown suburbs.

Living In

In her oral history of Black domestic workers in urban neighborhoods of Washington, DC, historian Elizabeth Clark-Lewis explored the mostly hidden world of white households and the Black social infrastructure upon which they depended. Clark divided the African American domestic workers into two classes: those who lived in and those who lived out.[12] The women who lived in were the exceptions to legally enforced rules prohibiting non-whites, Jews, and others from owning or renting properties in the neighborhoods where they worked.

Many racially restrictive deed covenants explicitly excluded Blacks and Jews. The earliest known covenant filed for Silver Spring, Maryland, prohibited selling or renting “to any person of African descent.”[13]

Others were more expansive, prohibiting “negroes or any person of negro blood…or to any person of the Semitic Race blood or origin… [including] Armenians, Jews, Hebrews, Persians and Syrians.”[14]

Frequently, the covenants included the provision, “this paragraph shall not be held to exclude partial occupancy of the premises by domestic servants.”

These “domestic servants” are the statistical anomalies in historical census data, skewing residential subdivisions that had 100 percent white ownership and tenancy by including small numbers of non-white residents.

Lucille Walker’s story had attuned me to the potential for recovering additional information about the Black workers living in rigidly segregated spaces typically identified as white. By 2022, however, I had collected many more accounts of the African Americans who worked in suburban white homes. And, I learned that I wasn’t the only one looking for this type of information. Barbara Bray also grew up in Silver Spring. Her father worked for the federal government and her mother was an acclaimed artist.

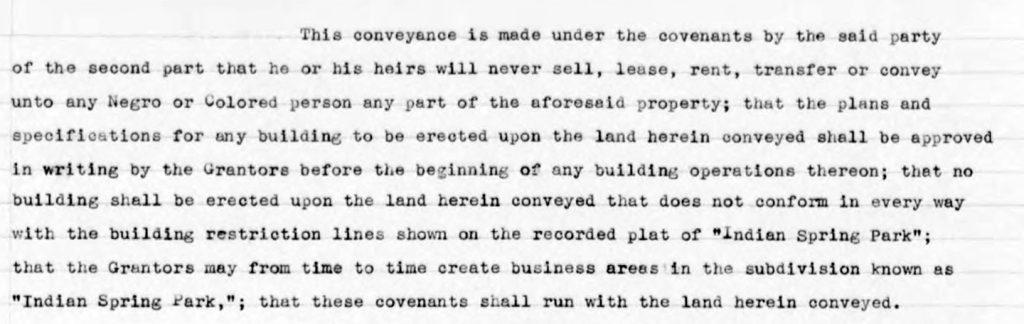

Bray’s parents, Erwin and Rosalie Ritz, moved from a Washington apartment to a suburban, brick, Cape Cod cottage in 1953. Built in 1937 in a subdivision platted a decade earlier, the Ritz home’s first deed had a racial covenant attached to it, binding owners to “never sell, lease, rent, transfer or convey unto any Negro or Colored person.”[15] Though unenforceable since the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer U.S Supreme Court case, the subdivision and its neighbors remained segregated until the 1960s.

“We lived in a Jewish community on Seminole Avenue and everyone was family there,” Bray explained in a 2022 interview. Her family had moved to one of several subdivisions near a country club that had been owned by a Jewish developer. The developer, Abraham Kay, also created several subdivisions. His club and subdivisions removed the barriers to Jews, but continued to exclude Blacks.

The Ritzes lived on Seminole until 1958, when the family moved to a larger house in another subdivision about four miles away. They lived in that home for six years. Two African American women worked for the family, cleaning house and helping to raise Bray and her sisters. Their names were Pearl and Lavinia. “I just don’t know why we never knew their last names. We never did,” Bray said.

Pearl lived with them and then Lavinia only came to the house during the day: “Pearl had a room in our first house on Seminole Street and she did everything for us.”

Unlike the Scandiffios, whose family photo collection includes prints and slides of Lucille Walker with the family, there are no corresponding photos documenting the Ritzes and the women who worked in their homes. Rosalie Ritz did, however, paint Lavinia’s portrait.

“It is on my wall. It’s five-by-six or something. It’s long and narrow,” Bray said. “We all loved Lavinia. We didn’t ever have a picture of Pearl.”

The painting and the memories of the two women stuck with Bray. For many years she had suspected that the suburbs where she grew up were different. At her high school in the 1960s, she recalled only one Black student in a student body of thousands.

“It’s like you’re kind of in, I don’t know like a cult…everyone is white around you. Everyone and there’s one Black person,” Bray explained. “And then I remembered when I think about it going home and there’s this beautiful Black woman taking care of me but I don’t know where she lives.”

Bray wrote about her memories in a 2021 blog post titled “Bearing Witness to Racism from a Privileged Perspective.” She was able to contextualize her memories after reading some of my work on Silver Spring as a sundown suburb. I found her 2021 blog post and reached out to ask her about it and her experiences growing up in white space.

“I was doing some research and I came across your work and that’s when I went, ‘Oh my God.’ I kind of knew before because of what happened to my parents, where they could live,” Bray said. The all-white schools, the all-white neighborhoods, and the antisemitism her family experienced all came into focus. “I didn’t understand how I was able to live in a Jewish community in Silver Spring.”

The Ritz family was among an embryonic Jewish community that moved to Silver Spring after World War II. The Jews who moved there navigated a suburban ecosystem defined by Jim Crow racism and deeply embedded antisemitism. Bray recalled the family home being vandalized. Around the same time, a newly established synagogue nearby experienced similar violence. White skin was just one part of a sort of multi-factor authentication system for full acceptance in sundown suburbs.

Labor Sheds

Ann Scandiffio thinks that Lucille Walker lived in Washington, DC. Barbara Bray believes that Lavinia lived in Lyttonsville. Located west of Silver Spring, Lyttonsville was a rural hamlet that grew up around a farmstead that a free Black man, Samuel Lytton, bought in 1853. Silver Spring absorbed Lyttonsville in the twentieth century. After Lytton died in 1893 and his heirs lost their property, a Washington real estate investor carved up the land. Stores, churches, and more homes appeared in the years bracketing the turn of the twentieth century.

Lyttonsville’s men farmed and they worked for government and private employers in surrounding Montgomery County and the District of Columbia. Work could be gotten at the nearby “National Park Seminary” and the Walter Reed Army Medical Hospital Annex. A local lumber and coal yard also employed many Lyttonsville men. Others became sanitation workers and a few opened their own businesses.

Many Lyttonsville women who worked outside of their homes became domestics. Some walked across the Talbot Avenue Bridge to spend their days cooking, cleaning, and caring for children in suburban white homes. Others lived-in.[16]

Black towns—hamlets, enclaves, and small cities—like Lyttonsville were extractive resources for white cities and suburbs. Whites exploited these Black spaces and their people. Whether through environmental racism (dumping, pollution, expulsive zoning), land theft, or labor, whites in neighboring communities preyed on Black communities to fulfill essential needs.[17] Women like Lucille Walker, Lavinia, and Pearl were integral parts of the sundown suburb’s racially segregated and liminal ecosystem.

Opportunities in Liminal Spaces

The Black women and men who ended up living in white spaces by virtue of their employment occupied a sort of liminal space between two worlds—white households and Black social infrastructure—first explored by Elizabeth Clark-Lewis in her oral history of early twentieth century Black domestic servants.[18] Beyond the urban neighborhoods in Clark-Lewis’s work there existed an even more complicated social and economic network in the suburbs.

Women left their husbands and families at one home and lived as exceptions in such legally defined white spaces as Northwood Park. They checked their individual identities at the white home thresholds. In their Black spaces, they were wives, mothers, aunts, and entrepreneurs. Inside the white homes where they worked, they became “domestic servants,” captive to a system that denied them access to education and economic opportunities outside of housework.

The white children raised in these homes have memories dulled by time and limited by the knowledge accessible to toddlers and adolescents. They are imperfect but nonetheless important keys to a larger vault of information on the power relations, paternalism, and racism that also occupied the homes.

There is much to learn from the women and men who lived in America’s segregated suburbs. Historians need to find their stories and tell them before it’s too late, before the last memories of living in liminal spaces are lost. We need the stories that these people and their children can still tell us to construct a more complete picture of American suburbs.