Guest column by Seth Biderman Washington Post August 24th 2025

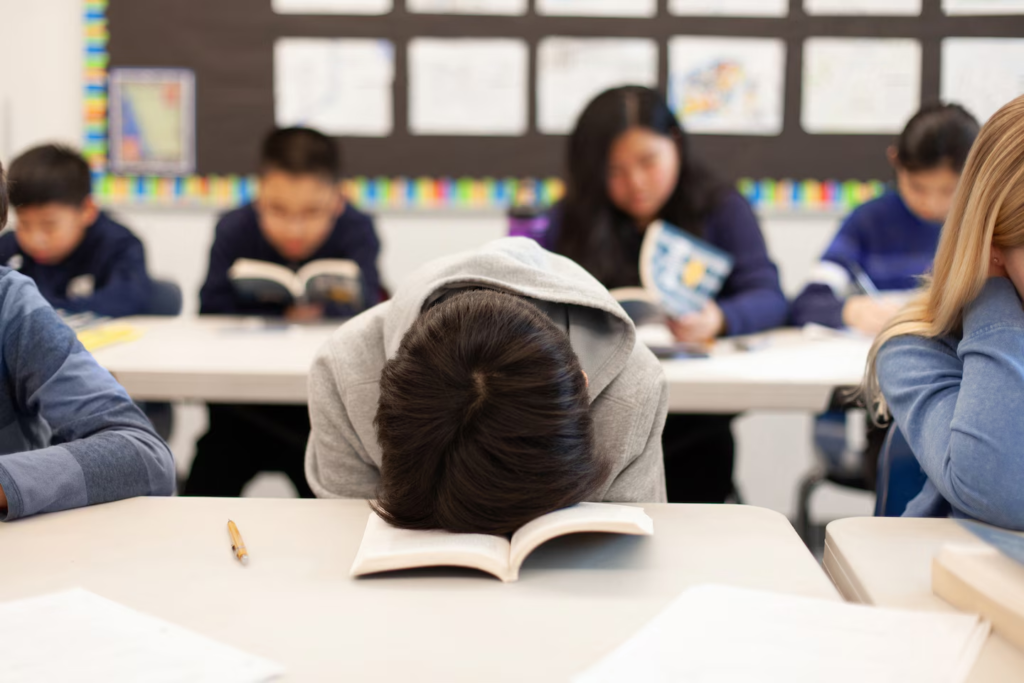

A few months into my first year of teaching middle-school English in Santa Fe, I realized that a handful of my students were not reading books. I had carefully structured the class time so there would be 20 minutes for silent, light-dimmed independent reading. Most of the students tucked into a novel at their desks or on the floor — an angsty adolescent novel or a dog-eared Harry Potter. But six or seven kids in my class of 20 would just sit at their desks and stare out the window. Or doodle on the back of their hand. Or unfold a paper clip and use it to make intricate carvings into an eraser. (Smartphones, the ultimate distractors, were not yet a thing.)

I would come up to these kids, and in a very gentle voice, remind them that they were supposed to be reading. Any book they wanted — it was their choice. But they did have to read.

The kids would sigh, lift themselves from their desks and shuffle over to the bookshelf. This I had stocked with all sorts of paperbacks from the thrift store and my own collection. The kids would look at the titles for a few seconds, grab one with a thin spine, shuffle back to their desks, open it up and wait for me to leave. Forty-five seconds later, they’d be once again window-staring or doodling or eraser-carving, the book lying sad and forgotten before them.

Like every English teacher who has ever walked this planet, I interpreted their resistance to reading not only as a pedagogical challenge but also as a personal affront. More: It was further evidence that civilization was in decline. What better way to learn about honesty and humility than to read “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”? What better way to understand compassion and tolerance than to read “The House on Mango Street”? What is life without “The Catcher in the Rye”?

There was also the lesser issue of the New Mexico state standards for English language arts, which I was legally obliged to insert into these half-formed human beings. These standards were full of proclamations like, “By eighth grade, students should be able to identify how an author employs metaphors to express key themes in a work of fiction.” Which those nonreader students would never learn by carving into their erasers.

I tried sticks and I tried carrots. I assigned mini book reports and punished the nonreaders with bad grades when they failed to produce. I created whole-class reading challenges, promising pizza parties if as a group we read so many books in a month. Following the advice of more experienced colleagues, I offered graphic novels and magazines to the nonreaders, just to get them started.

None of this worked. If anything, my efforts only made the nonreaders resent reading — and me — even more.

This problem kept me up at nights. I was 26 years old and fresh off a two-year stint at creative writing school. My secret ambition was admittedly naive: to become John Keating in “Dead Poets Society,” belting Walt Whitman from the desktops. Every minute a child did not read eroded my dream, left me defeated and gray.

Then I remembered my beloved 11th grade English teacher, Ms. Germanas. In her class, we had all read a book because she had made us do it. Each afternoon, we pulled our desks into a circle and read aloud “The Scarlet Letter.” No one had found much pleasure in “The Scarlet Letter,” but we had read every word of that book. All of us.

This approach flew in the face of my desire to create independent-minded students, motivated to read by their own love of literature and longing for human connection. But something had to give. I pulled the plug on independent reading and said that we were going to read a book, all of us together.

It was an unpopular edict, met with groans. The readers liked reading their own books, and the nonreaders liked carving their erasers. I held my ground, and that Friday afternoon the students came in to find the desks in a circle, and on each a copy of “Of Mice and Men.”

Yes, a book about two farmhands on a ranch in the 1930s, written by a White man now long dead.

“Here’s what’s going to happen,” I told them. “We’re going to read this out loud, page by page.”

One boy raised his hand and asked if he could read first.

“No,” I said. “I’m reading it to you.”

We opened the book, and I began.

It worked. Little by little, Friday by Friday, the nonreaders stopped window-staring and doodling. They wouldn’t always turn the pages, but they would listen.Advertisement

After a few Fridays, I noticed that one of the most inveterate nonreaders was not only listening, but also looking at his book, even mouthing along. On a hunch, I pulled him after class, showed him how quotation marks worked, and asked him to read Lennie’s lines the following week. He turned out to be a natural, with a slow, plodding delivery. Steinbeck would’ve been pleased.

As we proceeded, some of the reading kids asked if they could take the book home and finish it. I told them they could not. And if I caught them reading ahead in class, I would stop and make them come back to the page we were on.

With that one student reading Lennie and me reading the descriptions at a leisurely clip, it took us a few months of Fridays to move through that slim novel.

I taught English for another decade after that class. Each year, I was asked to spend less time on literature, more time training students to hunt down main ideas in snippets of informational text. Each year, I failed to comply, and kept reading novels out loud.

I don’t know what the next generation of English teachers has done. I don’t know if middle and high school students still circle up and listen to literature anymore.

What I do know is that I will never forget how the classroom was dark and still and quiet as we came to those final tragic pages of that Steinbeck classic. There seemed to be very little happening in the world outside the windows. “Le’s do it now. Le’s get that place now,” our Lennie read, slowly. Carefully. And I read on from there, and the classroom grew even quieter, the circle seeming to shrink, the distance between us dissipating, falling away. And then the final words, and we closed our books and sat there, 20 human beings in a circle, the unbearable weight of humanity draped over us like an enormous wool blanket, into which it was all woven in, rage and injustice, compassion and love.

Seth Biderman is a writer who lives in Washington, D.C. This is adapted and edited from an essay in his Substack, Unprincipalled, which draws from his former life as a teacher and principal.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/books/2025/08/20/reluctant-readers-teacher-steinbeck-read-aloud/