Students and advocates have expressed concern while pleading with lawmakers to invest more, despite budget cuts, toward mental health services in schools

Perspective by Theresa Vargas

Metro columnist April 19, 2023 at 3:43 p.m. EDT

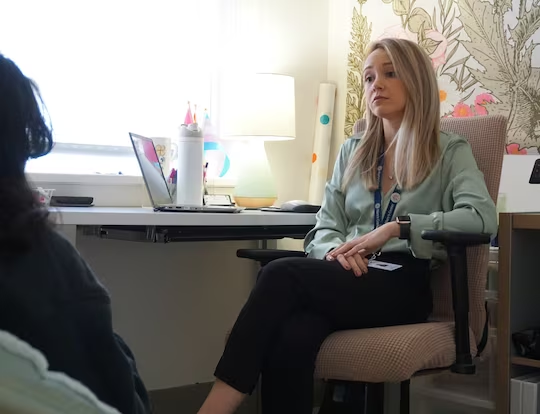

Last spring, Briana D’Accurzio was one of two mental health therapists at one D.C. school. This year, she is the only one. That’s not because fewer students at the school are experiencing anxiety and depression. That’s not because fewer students at the school are facing struggles at home or with their peers. And that’s not because fewer students at the school are harming themselves or contemplating suicide.

“The need is just as great as it was last year,” D’Accurzio told me on a recent morning.

The crisis in American girlhood

She explained that limited resources meant difficult decisions had to be made, and one of those decisions involved moving the other therapist to another D.C. school. That has left D’Accurzio alone to cover a school with nearly 1,600 students.

“If I was able to take all the referrals I get, I would have a caseload that is double, triple, quadruple what I have now,” she said. But she can’t take on every case, so she often has to refer students to clinicians outside of the school, and that process can mean scrambling and waiting, she said.

The kids are not okay. They are not okay in many places across the country, and they are not okay in the District. That should come as no surprise to anyone who has been paying attention to what students have been forced to face in recent years on top of normal childhood challenges: a pandemic that snatched from them loved ones and stability, gun violence that is taking from them classmates and a sense of safety, and an opioid epidemic that has left them contemplating carrying Narcan in hopes of keeping their peers from overdosing.

Children keep seeing grown-ups killed in the nation’s capital. They’re victims, too.

School-based therapists, educators and child advocates have seen up close how D.C. students are struggling, and they are worried. In recent weeks, I have spoken to some and listened to the testimony of others, and they have expressed a shared fear: that the city’s proposed budget could cause schools to lose crucial clinicians at a time when vacancies are already going unfilled.

“I can’t picture having less,” D’Accurzio said. “We need so much more, so thinking of having less is really scary.”

In recent weeks, advocates, educators and students have testified in front of city lawmakers, pleading with them to add $3.45 million to the proposed budget to sufficiently fund the community-based organizations that place mental health clinicians in schools across the city. The ask is small compared with the cost of failing those children, but it comes at a time when the city is looking to slash spending.

Schools brace for challenges as once-in-a-lifetime cash runs out

“In a year of tough choices, we urge you to continue to prioritize addressing the youth mental health crisis,” Judith Sandalow, the executive director of Children’s Law Center, said in testimony delivered at a budget hearing on Friday. “Unless there is sufficient funding to allow [community-based organizations] to continue to offer competitive pay, incentives and professional support to clinicians, the entire program is at risk.”

As proof of the need, Sandalow cited the findings of a 2021 DC Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Some of the data she noted: 28 percent of middle school students have seriously thought about killing themselves, about 12 percent of middle and high school students have taken prescription pain medicine without a doctor’s prescription, and more than 19 percent of middle school students and more than 25 percent of high school students reported that their mental health was “not good” most of the time or always.

Several students also testified on Friday, sharing their own experiences and calling on the city to add the funding to the proposed $19.7 billion budget.

One student described struggling to find a clinician in Southeast Washington. He said he goes to school every day but doesn’t have access to a therapist in the building. He said when he asked for places to get help outside of school, he was given locations nowhere near where he lives. “To me, this is unacceptable,” he said.

Another student spoke from inside a moving car. The high school sophomore said she had started cutting herself in middle school, and at 16 she still cuts herself and struggles to control her anger. She described meeting with clinicians over the years but never getting enough time to spend with any of them to open up. “Us youth are mentally struggling. Us youth are screaming for help,” she said. And there aren’t enough mental health professionals, she said, “to hear our cries.”

On a school day, a student sat inside D’Accurzio’s office. The 18-year-old didn’t want to share her name, but she wanted to talk about why it’s important for students to have access to therapists in schools.

Students face so much pressure to succeed and the world places so many problems in front of them that they need a space where they can talk to someone without judgment, the teenager said. She described getting that when she walks into D’Accurzio’s office. The teenager said she often advises friends and relatives to take care of their mental health needs.

“It shouldn’t be something you should be ashamed of,” she said. “It shouldn’t be something we put aside for later. It should be a number one priority.”

She’s right — the mental health needs of the city’s children deserve to be prioritized. D.C. lawmakers will have to make some difficult decisions before finalizing the budget, but providing enough funding to make sure schools don’t lose clinicians should be a no-brainer.

D’Accurzio works for Mary’s Center, a community organization that has placed clinicians in more than two dozen D.C. schools. On the hard days, D’Accurzio said, she thinks about the students who have stepped into her office with complex needs and have successfully graduated out of therapy. Some have told her, she said, “I didn’t see myself alive at this time.”

“If we didn’t have mental health professionals in the schools to attend to their needs, I worry what their future would look like,” she said. If schools lose clinicians, she added, that “would be detrimental to the entire community. It would be detrimental to the students we’re servicing. It would be detrimental to their families.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/04/19/schools-therapists-dc-budget/