In a rare, salted-paper photograph, Frederick Douglass wears a sophisticated high collar, an elegant three-piece suit and a short salt-and-pepper Afro, coifed with a part down the middle of his scalp. Douglass, who would become one of the most photographed people of the 19th century and one of the country’s most powerful orators, appears in the faded photo with a righteous gaze, in a pose that the writer and activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton described as “majestic in his wrath.”

This photograph, taken in 1860 and unique in style among the dozens of images often seen of Douglass, is showcased in the exhibit “One Life: Frederick Douglass,” which opened last month at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

At 88, he is a historical rarity — the living son of a slave

The exhibit traces Douglass’s trajectory, in photographs, records and writings, from enslaved man to fugitive, fierce abolitionist and presidential adviser, highlighting how he carefully constructed his enduring image using every available medium of his time.

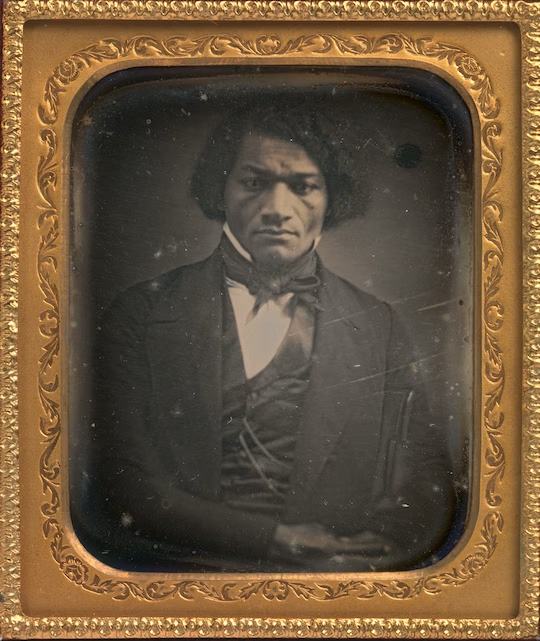

Douglass, seen around 1845. “He wanted to create a dialogue with his photograph,” curator John Stauffer said. (Onondaga Historical Association Museum & Research Center)

“Douglass, in the larger sense, cultivated an immensely powerful voice in different registers. One was as speaker, one was based on his photographs and prints, one was through his activism and one was through his writing,” said Smithsonian guest curator John Stauffer, a professor of English and African and African American Studies at Harvard University.

“He believed a photograph was an accurate representation of the figure,” Stauffer said. “He always dressed up for his photography, much like he did for his speeches. He wanted to create a dialogue with his photograph that he provided with his speeches. It was a form of representation he hoped would convince people to follow him in advocating for equality.”

Frederick Douglass had nothing but scorn for July Fourth

Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in 1818, on a Maryland plantation owned by Edward Lloyd V, a former governor of Maryland and U.S. senator. The Smithsonian exhibit includes the original leather-bound ledger containing the names of babies born on that planation. On the left displayed page, in black ink and large script, overseer Aaron Anthony wrote: “Frederick August son of Harriett Feby 1818.” No father was mentioned; some historians suspect it was Anthony.

In September 1838, Frederick Bailey escaped enslavement, changing his name to Frederick Douglass. A 19th-century flier in the exhibit depicts a painting of a young Frederick escaping barefoot — though in the real-life escape he wore shoes. The illustration is headlined: “The Fugitive’s Song,” which was composed and dedicated to Douglass. The caption reads: “Frederick Douglass, A Graduate from the ‘Peculiar Institution.’ For his fearless advocacy, signal ability and wonderful success in behalf of HIS BROTHERS Ind. BONDS. And to the FUGITIVES FROM SLAVERY in the UNITED STATES & CANADA.”

On Sept. 15, 1838, Frederick married Anna Murray, a free Black woman who had lived in Baltimore and helped him escape enslavement, financing his escape by selling a bed made of feathers. The couple went on to have five children together.

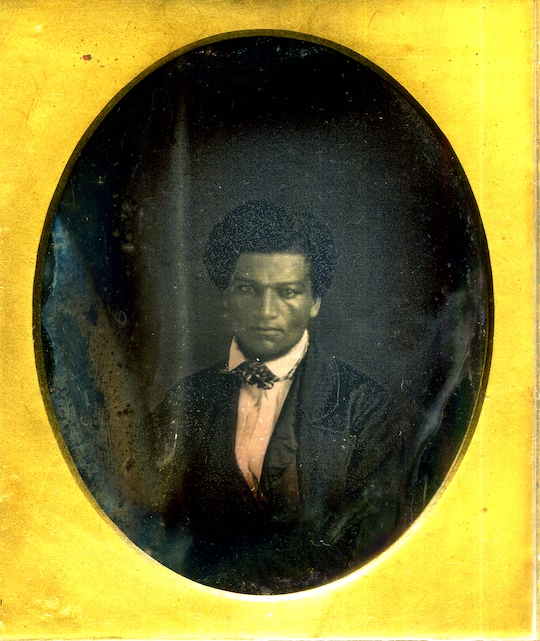

Douglass in a daguerreotype circa 1841, the year he was hired as a speaker for the American Anti-Slavery Society. (Collection of Greg French)

The Smithsonian exhibit, which runs through April, includes one of the first known photographs of Douglass, taken in 1841. The image, tucked inside a worn frame encased with a red silk lining, shows a young Douglass with his thick black curls piled high, his jaw square and an intense stare. It was captured a year after the first commercial daguerreotype studio opened in the country, the National Portrait Gallery says, when the exposure time for such a machine “could run up to 15 seconds.”

The searing photos that helped end child labor in America

Douglass was hired that year as a speaker for the American Anti-Slavery Society, moving with his young family to Lynn, Mass., near Boston. For the next 60 years, Douglass would make his mark on the world, becoming one of the most powerful voices against the cruel institution of chattel enslavement. He wrote hundreds of essays, a novela, three autobiographies and thousands of speeches.

“When he escaped from slavery, he dated his birth to the day he escaped from slavery,” Stauffer said. “So, he felt like, ‘I’m playing catch up. I have to make up for all these lost years.’ He was a workaholic. He read voraciously. He got caught up on this kind of canon of what any educated person needs to read. He was passionate about it.”

An oil painting of Douglass, circa 1845, when he published his first autobiography. (Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery)

Douglass knew one of his greatest tools was public speaking. For those who could not attend his speeches, he published them in his newspaper or in pamphlets. William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the Liberator newspaper, advertised and published Douglass’s 1845 autobiography, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.”

Frederick Douglass delivered a Lincoln reality check at Emancipation Memorial unveiling

The autobiography was a hit, making Douglass so famous that he had to flee to Great Britain to avoid being enslaved again as a fugitive. Abolitionists helped buy his “freedom,” and Douglass returned to the states two years later, in 1847, as a free man. He moved to Rochester, N.Y., where he founded the North Star, an anti-slavery newspaper whose name referred to the light “that helped guide those escaping slavery to the North,” according to the Library of Congress. Douglass, in the initial issue, called it “the STAR OF HOPE.”

In 1855, Douglass published his second autobiography, “My Bondage and My Freedom: Part I. — Life as a Slave. Part II. — Life as a Freeman.” An original copy of that book, published during the period when violence had erupted between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions vying for control of the new territory of Kansas, lies beneath a glass case in the Portrait Gallery.

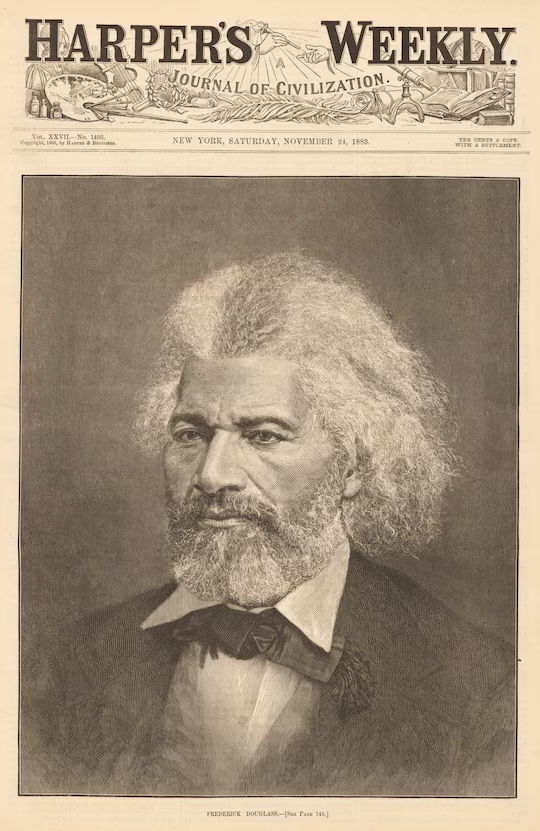

John White Hurn took the most photographs of Douglass — and also helped him flee after the Harpers Ferry raid. (Collection of Greg French)

One of the most striking photos in the exhibit shows Douglass with a shock of white hair, growing like a painted line in his black Afro. The photograph was taken by John White Hurn, most likely on Jan. 14, 1862, according to curators. Douglass had given a speech at the National Hall in Philadelphia, located a block from Hurn’s studio.

Hurn, a telegraph operator who had helped Douglass flee again in 1859, after his abolitionist ally John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, went on to photograph Douglass again in 1866 and 1873. Hurn took as many as nine photographs in all, the most of any Douglass photographers.

‘Unflinching’: The day John Brown was hanged for his raid on Harpers Ferry

After the Civil War began in 1861, Douglass wrote to President Abraham Lincoln advocating that he free all enslaved Black people in America and provide them with arms to fight against the Confederacy. The two met, at the White House, on several occasions.

The Smithsonian exhibit contains an original copy of a letter dated Aug. 29, 1864, in which Douglass asked the president to send a Black agent to conduct “squads of enslaved people northward.” Douglass demanded that the Union Army provide food and shelter for the Black freedmen. Lincoln listened. Days later, the Union army marched to victory in Atlanta.

Frederick Douglass needed to see Lincoln. Would the president meet with a former enslaved person?

“He said in his speeches this is a golden opportunity to destroy slavery and remake the United States as a true democracy,” Stauffer said. “He charged Lincoln: ‘End slavery right now. Free them and arm them. They know the South far better than anyone else.’ Had Lincoln and his administration heeded that advice, I actually think the war would have lasted far less than four years. Lincoln and his generals — some of them had been racist — realized the only way they could win this war was with the support of Blacks.”

Douglass wrote many of his powerful speeches at his home, Cedar Hill, in Southeast Washington, which he bought in 1877, defying laws that prohibited African Americans from buying property in the area. The home, now part of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, will reopen to the public Tuesday, the National Park Service announced, after closing in 2020 for the pandemic and renovations.

The reopening ceremony will include a dramatic performance of Douglass’s 1852 speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Douglass, in an engraving from 1883. (Jen Harris/National Portrait Gallery)

Stauffer said one of his objectives in collecting the photographs in one exhibit was to help people feel the weight of Douglass’s legacy.

“He was the preeminent writer and widely known in his day as the greatest orator in the 19th century,” Stauffer said. “It captures Douglass’s significance as a leader. He had an unmatched orator style. He was blessed with musicality; he had a musical voice. He could adjust the range. He was a wordsmith. He was dedicated to giving speeches that would keep audiences on their seats, wanting to follow every word.”

Frederick Douglass died Feb. 20, 1895, just hours after his public makeup with Susan B. Anthony

Douglass knew, he said, that “words are one of the most potent weapons one could have in trying to achieve equality and the true vision of democracy.”

By DeNeen L. BrownDeNeen L. Brown, who has been an award-winning staff writer in The Washington Post Metro, Magazine and Style sections, has also worked as the Canada bureau chief for The Washington Post. As a foreign correspondent, she wrote dispatches from Greenland, Haiti, Nunavut and an icebreaker in the Northwest Passage. Twitter