Posted on February 19th, 2025

Political changes can create uncertainty and stress, not just for adults but for children as well. Shifts in policies, leadership, and societal discussions can impact their sense of stability, leading to feelings of anxiety, confusion, or fear. During these times, it’s key to provide children with the emotional support and reassurance they need to navigate their feelings in a healthy way.

Understanding Children’s Emotional Responses to Political Changes

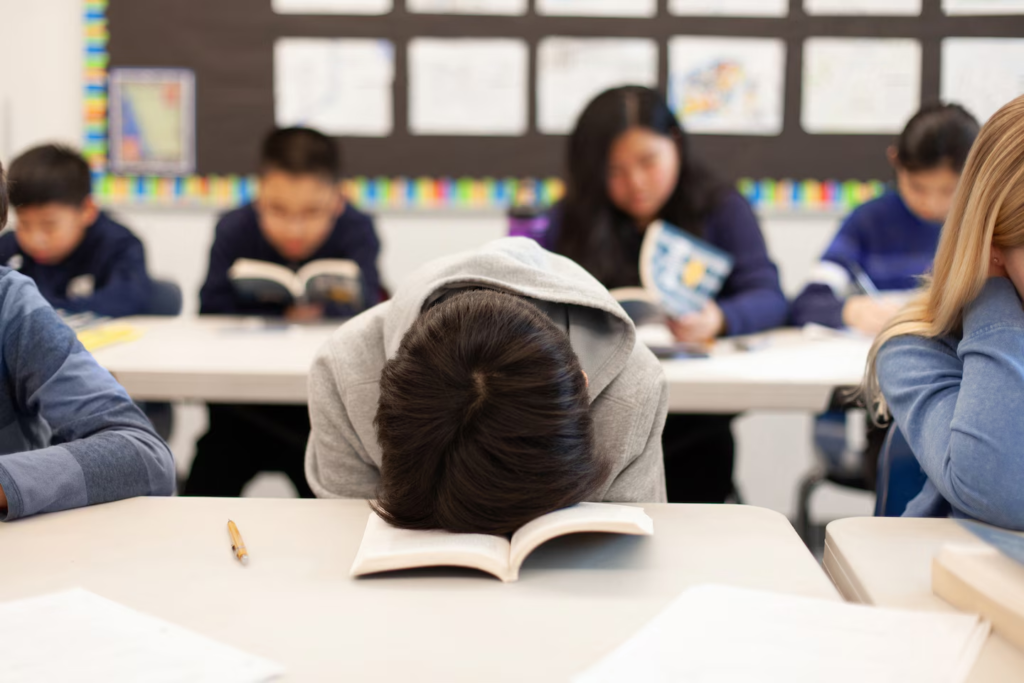

Learning about children’s emotional responses to political changes is key for addressing their feelings and supporting their mental health during these times. Children may react with anxiety when they sense that their normal routines and environments are disrupted. Such responses might be more pronounced in children who overhear conversations among adults or see distressing news reports.

They could become unusually clingy, experience stomachaches, or have trouble sleeping. Fear can also manifest, especially when children sense hostility or tension around them, even if they don’t fully grasp the political issues at play. Younger children, in particular, may feel confused about what they see and hear because their cognitive abilities to process complex events are still developing.

Children’s perception of political changes varies significantly across different developmental stages, affecting how they absorb and react to what’s happening. For example, toddlers and preschoolers may not understand the specifics of political events but can pick up on cues from adult conversations and the overall emotional climate at home. Maintaining a calm environment helps reassure them.

The Impact of Politics on Children

Politics can have a significant impact on children, shaping their views and experiences in various ways. From policies and laws that directly affect their lives to the overall political climate in their communities, children are constantly influenced by the world of politics. Here’s the various ways in which politics can impact children:

- Political policies and laws can greatly impact the daily lives of children, from education to healthcare and beyond.

- The political climate in a community can shape a child’s understanding of diversity, inclusion, and social issues.

- Media coverage of political events and campaigns can expose children to complex ideas and ideologies at a young age.

- Children from politically involved families may feel pressure to conform to certain beliefs or values.

- Political discussions and debates in schools can help children develop critical thinking skills and learn about different perspectives.

It is important for adults to be mindful of the impact of politics on children and to have open and age-appropriate conversations with them about current events and political issues. By understanding the influence politics can have on children, we can help encourage and support them in handling the complex world of politics.

Providing Reassurance and Stability

In today’s society, political changes are inevitable. These changes can have a significant impact on children, causing them to feel confused, anxious, and even afraid. As parents, it is our responsibility to help our children understand these changes and provide them with a sense of security and stability. One way to do this is by nurturing strong emotional connections within the family. Here are some tips to help you do just that:

- Communicate openly and honestly with your children about political changes and their potential impact.

- Encourage your children to share their thoughts and feelings about these changes without judgment.

- Validate your children’s emotions and let them know that it is okay to feel scared or uncertain.

- Take the time to listen to your children and address any concerns or questions they may have.

- Engage in activities as a family that promote bonding and togetherness, such as game nights, movie nights, or outdoor adventures.

- Create a safe and welcoming home environment where your children feel comfortable expressing themselves.

- Lead by example and show your children how to handle political changes in a calm and respectful manner.

- Remind your children that no matter what happens in the world, they are loved and supported by their family.

By following these tips, you can help cushion the effects of political changes on your children and strengthen the emotional connections within your family. As always, your love and support are the most important things you can provide for your children during these uncertain times.

A Call to Action for Supporting Children

This call to action for support involves everyone — parents, teachers, community members, and political figures. In your community, rally behind initiatives that prioritize children’s mental health support during political transitions. A unified approach can significantly strengthen efforts to establish safe environments where children thrive despite ongoing changes. Foster dialogues with local leaders and school boards to make sure that the well-being of children is at the forefront of policy discussions. Advocate for school programs that address emotional intelligence and stress management, as these can provide children with important tools to express their emotions.

Your individual efforts, combined with those from community organizations, can also uplift children in need. Non-profits that focus on child mental health, like those occasionally involved in clothes distribution, play a key role in providing necessary resources and support. Lending your time or resources to such organizations not only strengthens social safety nets but empowers children through collective efforts during political shifts. Facilitating conversations about these non-profits within your networks spreads awareness and potentially garners more support.

Conclusion

Supporting children through political changes is not just critical; it’s a shared responsibility that ties us all together. From the quiet moments of reassurance at home to the concerted efforts of community initiatives, every action counts. Crisis times can lead to heightened anxieties in children, which is why focusing on their mental well-being becomes indispensable. Donations and clothes distribution play a pivotal role here, offering practical support while fostering a sense of belonging and security. When children face uncertainty, knowing they have a robust and caring network can make all the difference.

Can you visualize the profound impact of your involvement? With a little help from everyone, at Josie’s Closet Inc, we can lay a solid foundation for the peaceful future our children deserve. Even small contributions of time or resources can extend a safety net for children whose families need a bit of extra support. By supplying them with necessities like clothing and guidance, we not only address immediate needs but build lasting connections and empower these young minds.

Now is the time to make a tangible difference. Take action now! Support children’s mental health by donating to Josie’s Closet and help us create a stable, nurturing environment for children in need during political changes. Your support provides key resources that guarantee that children can stand resilient and hopeful as they cope with their complex world. Reach out to info@josiescloset.org for more ways to get involved and lead your children on this meaningful journey.

https://josiescloset.org/blog/supporting-children-s-mental-health-during-political-changes

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/9-things-to-do-when-you-feel-hopeless-5081877-noicons-9c0d5df035bd4e0f9b61a5c5dbc25336.png)